Follies: Of No Use but Delight!

By Barbara Israel

Last fall while exhibiting at the Delaware Antiques Show I decided to visit the gardens of our historic house sponsor, Winterthur. I knew they had a special exhibition called “Follies: Architectural Whimsy in the Garden” and was curious to see what sorts of extravagances would be shown. Many people, myself included, are unsure about what exactly defines a folly. Is it a gazebo or a garden pavilion? How about a tower…or a tent? Can it be a grotto? Or can any outbuilding qualify as a folly? In fact, all of these structures can be designated as a “folly” as long as they aren’t currently serving as a dwelling (that rules out hermitages!) or performing any other useful purpose. Follies are all about being wholly designed for decorative aims.

Have you ever been lost in a 60-acre garden? As I was in a hurry to get back to my show booth I walked around with great vigor determined to find all examples of these unusual creations. However, my navigation skills were lacking and after an hour or so I ended up using Google maps to find myself!

You cannot miss the first one, the Needle’s Eye, a pyramidal form floating in a pond by the main driveway. Not all of the Winterthur follies have a historical precedent but this one derives from an 18th-century example in South Yorkshire. Its perfect reflection combined with the array of curious ducks swimming about made this a very memorable vision. It certainly fulfills Winterthur’s prerequisite of “architectural constructions…positioned within the landscape to…pique your curiosity.” Interestingly, according to local legend the original Needle’s Eye was created circa 1730 for the Marquis of Rockingham who, having made a wager that he could drive his horse and carriage through the eye of a needle, hired a mason to build a pyramid with an opening wide enough to accommodate a small carriage…oh, those crazy 18th-century aristos!

After a good climb through the property’s Azalea Woods I glimpsed the Neoclassical Folly through the trees. Its description on the explanatory stand said it was “modeled after the portico, or entrance, to a Greek temple or public building.” I found this folly’s orange interior totally eye-catching and noted that the pair of armchairs (as expected stylistically on point), placed side by side frontally, compelled their occupants to engage the surrounding view, which is, of course, another aim of these decorative buildings.

After a good climb through the property’s Azalea Woods I glimpsed the Neoclassical Folly through the trees. Its description on the explanatory stand said it was “modeled after the portico, or entrance, to a Greek temple or public building.” I found this folly’s orange interior totally eye-catching and noted that the pair of armchairs (as expected stylistically on point), placed side by side frontally, compelled their occupants to engage the surrounding view, which is, of course, another aim of these decorative buildings.

Without any question I found the next structure the most difficult for my old-fashioned eye to appreciate, as it was the least traditional of all. Though the form could be considered traditional since it was described as an “interpretation of the porte cochere, or covered entrance, to Winterthur’s charming train station”, its mirrored surface and bold white benches gave it a distinctly contemporary vibe. It’s truly fabulous in terms of today’s aesthetic and is a perfect folly in that it is a costly, ornamental building with no practical purpose.

I moved on across the field to what appeared to be the first permanent structure I’d seen, a brick, hexagonal, open-sided building. From the description I found out that it was called Brick Lookout and had been installed intentionally as a folly by Mr. Henry Francis du Pont in the 1960s, reusing the peaked tin roof and eagle finial from an old shed. In my opinion it was a very successful addition to the landscape.

I moved on across the field to what appeared to be the first permanent structure I’d seen, a brick, hexagonal, open-sided building. From the description I found out that it was called Brick Lookout and had been installed intentionally as a folly by Mr. Henry Francis du Pont in the 1960s, reusing the peaked tin roof and eagle finial from an old shed. In my opinion it was a very successful addition to the landscape.

After a few false starts I came upon the Bristol Summerhouse, another of Mr. du Pont’s follies. In 1960 he commissioned this copy of a Bristol, RI summerhouse that he had seen and admired. It is situated to present a breathtaking vantage of sweeping hills and shining ponds and offers the viewer a sheltered place, protected by louvered shutters, to sit and enjoy the vast countryside. True to form Mr. du Pont re-used old brick for the flooring.

As I walked down the hill it was impossible to miss the unlikely folly at the bottom and I found myself wondering aloud, “Really?” But I was on my way to learning that even tents had been follies in landscape gardens. This was Winterthur’s Ottoman Tent! Once inside the Ottoman Tent it was very clear to me that this was the most inviting interior and it would be the ideal setting for the intimate soirée that I can only dream of giving! The background on the Ottoman Tent stated that the influence of exoticism on Northern Europe in the 1700s created a demand for certain novel design elements from the Ottoman Empire (today’s Turkey). The owner of Painshill in Surrey, the Hon. Charles Hamilton (1704-1794), installed a pseudo-tent folly that was “brick and plaster swaddled in canvas to look like a tent.” Actually, Hamilton placed a number of variously themed follies on his property. The most piquant detail I discovered was that in true folly fashion his Hermitage was a pure fantasy as an individual was employed as its hermit. Shockingly, though hired to a 7-year contract, he was fired soon into his tenure for absenteeism!

In the Enchanted Woods, a children’s garden, I came upon the Faerie Cottage, one of the permanent, though not original Winterthur follies. It was created from found materials on the estate. There is an authentic early wellhead near the openwork log entrance structure and a pair of stone benches with carved backs depicting whimsical angels. But there are far more fanciful details. I saw six pairs of silk butterfly wings hanging on hooks and a sign reading “Happy times are never ending when we’re playing and pretending! Please return wings to the Faerie Cottage so that others may enjoy. Thank you!” Next to the Cottage is an example of the best use ever for the stump of a tulip tree. It’s a mini folly on its own! The charm of the Faerie Cottage and its surroundings were clear to me and I can only imagine their effect on a child.

I escaped from the Enchanted Woods and came upon the Gothic Tower. Large, expensive towers were added to gardens in the 18th and 19th centuries in the UK and Northern Europe. Winterthur’s Gothic Tower has a dual-purpose veneer of blackened or charred wood that adds to its imposing appearance while enhancing its durability to last until the exhibition’s January 5, 2020 closing. I took the bait and climbed the tower to see if it afforded an impressive view (below right) as is the promise of “folly” towers. It certainly delivered!

I escaped from the Enchanted Woods and came upon the Gothic Tower. Large, expensive towers were added to gardens in the 18th and 19th centuries in the UK and Northern Europe. Winterthur’s Gothic Tower has a dual-purpose veneer of blackened or charred wood that adds to its imposing appearance while enhancing its durability to last until the exhibition’s January 5, 2020 closing. I took the bait and climbed the tower to see if it afforded an impressive view (below right) as is the promise of “folly” towers. It certainly delivered!

At this point though I was in sight of the mansion I managed to get myself totally lost thereby missing a number of follies that were near the house including three permanent fixtures that had been installed by Mr. du Pont: two were rescued from the nearby Latimeria estate in 1929 and the 1750 House was a reclaimed facade from a New Castle, DE house.

In his gardens Mr. du Pont was visionary in realizing the value of repurposed elements. Even though I didn’t see the “Green Folly” it is absolutely worth mentioning. In the tradition of the 18th-century English landscape garden it is constructed entirely of natural elements sourced from the Winterthur garden. While their description says it ”represents the spirit of the garden”, it is “green” in 21st-century parlance, while also harking back to the English Garden style.

The “Chinese Pavilion” folly has an English antecedent, inspired by the Chinese House in the Stowe Landscape Garden in Buckinghamshire. This beautiful building is a jewel box with copies of the interior wallpaper of Winterthur’s Chinese Parlor decorating the exterior.

The “Chinese Pavilion” folly has an English antecedent, inspired by the Chinese House in the Stowe Landscape Garden in Buckinghamshire. This beautiful building is a jewel box with copies of the interior wallpaper of Winterthur’s Chinese Parlor decorating the exterior.

Since my brief and hurried tour of Winterthur’s gardens I have discovered that the UK has an organization, the Folly Fellowship, founded in 1988 by Andrew Plumbridge. It is dedicated to the protection, promotion and preservation of Britain’s follies. Their website has a myriad of information on the entire world of follies–a comprehensive definition of “folly” with examples, follies for sale, folly designers, folly events, publications about follies–truly this is your source for any folly-related query or need. For more information visit the Fellowship’s website. Americans can join as overseas members for £65 a year.

And if you find yourself in the Wilmington area in the next year you should make a trip to Winterthur for a first-hand experience of these amazing structures. Visit the Winter website for information about this exhibtion or to buy tickets.

The Exhibition of American Sculpture, April-August 1923: Part II

By Eva Schwartz

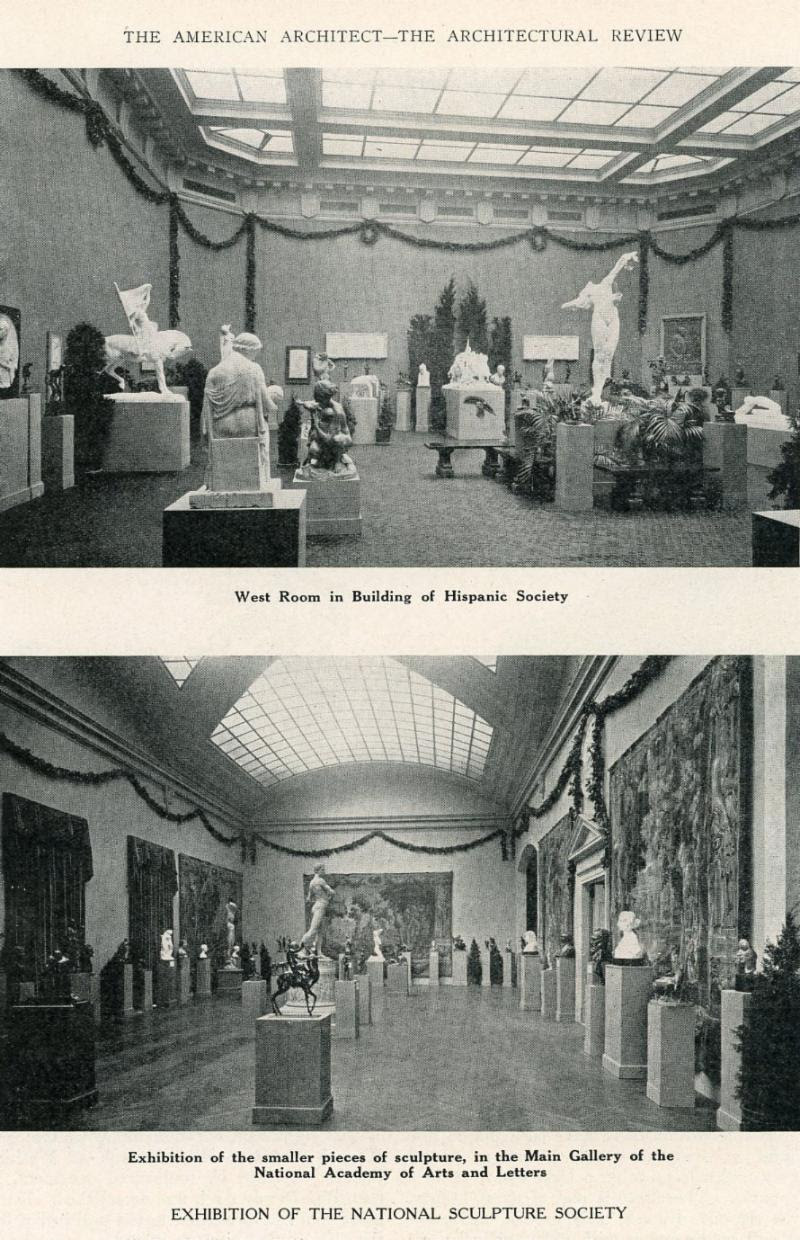

The organizers of the 1923 “Exhibition of American Sculpture” had one overarching goal: that sculpture be afforded the recognition it deserved. So they must have been pleased that by the time the show opened to the public on April 14th, there had already been considerable buzz. The editor of The American Architect and the Architectural Review wrote on March 28th that, “For more than a quarter of a century, the National Sculpture Society has been quietly but forcefully working to promote the progress of the sculptor’s art. The announcement recently made by the [Society] that it will hold an…exhibition in New York in April is one of considerable importance…[since] sculpture, the pure embodiment of form, is not so widely seen nor is it even half appreciated…[In fact], the public will have to be taught the value of form in sculpture”. With its unprecedented assemblage of nearly 800 sculptures by American artists, the National Sculpture Society intended to do just that. (Photos: Top – National Sculpture Society exhibition at the Hispanic Society, Spring 1923, courtesy National Sculpture Society. Bottom – View from the plaisance to the main terrace, International Studio, June 1923.)

Thankfully, the city’s most important newspapers heartily supported the cause. On April 13th, The New York Times art critic, Elisabeth Luther Cary (1867-1936), lauded the show as “the first of its kind in magnitude and appropriate setting…the first big open air sculpture exhibition ever to be given in America”. Cary noted “the great enthusiasm among the first day’s visitors” and remarked on the care with which the grounds of the Audubon Terrace had been “metamorphosed” into the most pleasing gardens. The landscape architect, Ferruccio Vitale (1875-1933), had skillfully transformed the imposing stone terraces with carefully placed trees, flowering shrubs, and substantial areas of green lawn. Cary described the scene:

Pink rambler roses looking a little like loved children let out too early in their summer clothes, were everywhere, nodding their heads through the massive iron bars of the big fence at the entrance to the grounds on Broadway, and here and there, everywhere through the entrance court on the main terrace, and down the stairway in the plaisance and garden, mingling with gay blossoms of spring bulbous plants, with hydrangeas and lilacs. Against the walls of the buildings were flowering shrubs with here and there evergreens. Some of these shrubs, good sized trees, were just coming into blossom and others showed only the faintest suspicion of buds and with warmer weather will grow more beautiful day by day.

The New York Evening Post’s critic, Margaret Breuning, who called the show the “most important single event on the crowded art calendar”, was similarly smitten with the setting of the exhibition, and with the profusion of plants and trees on display. In her April 12th review, she commended Vitale and his partners for having so beautifully enlivened the otherwise austere terraces with quantities of lilacs, pink spirea, and rose bushes. Her first reaction, upon entering the show, was that “now at last sculpture has a chance; it does not have to act as an adjunct of some other exhibit, but takes its place as the piece de resistance”. Breuning further noted that the exhibition brought together works from “virtually every important living American sculptor” and that it was “astonishing, perhaps, for the casual visitor to realize what proportions the art of sculpture [had] attained in America”.

The New York Herald also praised the exhibition in an April 13th review, commenting particularly on the attractiveness of the terraces:

The little garden and terrace of the Hispanic Museum have been completely transformed and the combination of the sculptures with the masses of flowers and plants makes such a pleasing effect that doubtless a strong effort will be made to have this exhibition an annual affair. On the upper terrace the heroic figures and large groups are interspersed with formal greens but in the garden below there is an opportunity to contrast the fountains and statues with lawns and flower beds, which have been designed to give an aspect of permanence.

What an ingenious concept—to imbue a temporary exhibition with an aspect of permanence! Ferruccio Vitale’s insistence on using full-grown trees and shrubs and installing lawns that looked as if they’d always been there spoke to the enduring importance of sculpture, and of art itself. There was a weightiness about it that resonated with visitors. But there was also a sense of playfulness, and of renewal, exemplified by the abundance of spring blooms. Knowing as we do that Vitale and his team pulled this show together in only a few months’ time– and without knowing exactly which works would be shown and where—makes it all the more marvelous that this sense of permanence was achieved. (Photos: Broadway entrance seen in 1926 and today. Archival photo by Brown Brothers from the collection of the New York Public Library. Color photo from Google Maps.)

What an ingenious concept—to imbue a temporary exhibition with an aspect of permanence! Ferruccio Vitale’s insistence on using full-grown trees and shrubs and installing lawns that looked as if they’d always been there spoke to the enduring importance of sculpture, and of art itself. There was a weightiness about it that resonated with visitors. But there was also a sense of playfulness, and of renewal, exemplified by the abundance of spring blooms. Knowing as we do that Vitale and his team pulled this show together in only a few months’ time– and without knowing exactly which works would be shown and where—makes it all the more marvelous that this sense of permanence was achieved. (Photos: Broadway entrance seen in 1926 and today. Archival photo by Brown Brothers from the collection of the New York Public Library. Color photo from Google Maps.)

The show certainly made an impression, right from the start. The exhibition kicked off just outside the Audubon Terrace gates at 156th Street, on the grassy median that cut through Broadway. There, as a signal to passersby, was an elaborate flagpole base by Leo Lentelli (1879-1961). As the median was city property, Archer Huntington (1870-1955), the exhibition’s benefactor, telephoned Francis Gallatin (1870-1933), the Parks Commissioner, to beg the use of it; happily, it was granted. Unfortunately there isn’t a photo of Lentelli’s flagpole, though it must have been striking. The New York Times reporter called it “a delightful foreword to the exhibition, a poster announcing it, so to speak”. From there, guests made their way through the gates into the entrance court, where there were thirteen sculptures on display. (Photo: The American Architect and Architectural Review.)

The show certainly made an impression, right from the start. The exhibition kicked off just outside the Audubon Terrace gates at 156th Street, on the grassy median that cut through Broadway. There, as a signal to passersby, was an elaborate flagpole base by Leo Lentelli (1879-1961). As the median was city property, Archer Huntington (1870-1955), the exhibition’s benefactor, telephoned Francis Gallatin (1870-1933), the Parks Commissioner, to beg the use of it; happily, it was granted. Unfortunately there isn’t a photo of Lentelli’s flagpole, though it must have been striking. The New York Times reporter called it “a delightful foreword to the exhibition, a poster announcing it, so to speak”. From there, guests made their way through the gates into the entrance court, where there were thirteen sculptures on display. (Photo: The American Architect and Architectural Review.)

We know from the minutes of the exhibition committee’s December 12th meeting, that Ferruccio Vitale intended to use the entrance court as a place of honor, where some of the most extraordinary works by some of the most celebrated sculptors would be shown. Fittingly, the sculpture at the center of the court was a plaster casting of Daniel Chester French’s Memory (the original conceived 1886-87, revised 1909, and carved 1917-19). French (1850-1931) was the Honorary President of the National Sculpture Society at the time, and considered (even today) to be one of the most gifted of all American sculptors. The original work, which considers the fleeting nature of life and beauty, was acquired by The Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1919, and can still be seen on view in the American Wing. It was carved by the Piccirilli Brothers, the renowned family of carvers responsible for giving form to the majority of French’s works. Royal Cortissoz, the acerbic critic for the New York Tribune, wrote in the April 22nd edition that “for many years Mr. French has been known chiefly for commemorative monuments. Then in the winter of 1919 there emerged from his studio the great marble of Memory…a superb study of the nude, lifted by imagination to a high plane”. The New York Times Magazine noted on April 15th: Another nude figure of rare quality is Memory, by Daniel Chester French. The rhythms here are slow in cadence, the figure is an image that answers to a true idea, stimulates deep reflection and soothes a disturbed spirit. This again is eloquent of Greek heritage and the power of classic art to make one forget all the madness and severity of human life.

We know from the minutes of the exhibition committee’s December 12th meeting, that Ferruccio Vitale intended to use the entrance court as a place of honor, where some of the most extraordinary works by some of the most celebrated sculptors would be shown. Fittingly, the sculpture at the center of the court was a plaster casting of Daniel Chester French’s Memory (the original conceived 1886-87, revised 1909, and carved 1917-19). French (1850-1931) was the Honorary President of the National Sculpture Society at the time, and considered (even today) to be one of the most gifted of all American sculptors. The original work, which considers the fleeting nature of life and beauty, was acquired by The Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1919, and can still be seen on view in the American Wing. It was carved by the Piccirilli Brothers, the renowned family of carvers responsible for giving form to the majority of French’s works. Royal Cortissoz, the acerbic critic for the New York Tribune, wrote in the April 22nd edition that “for many years Mr. French has been known chiefly for commemorative monuments. Then in the winter of 1919 there emerged from his studio the great marble of Memory…a superb study of the nude, lifted by imagination to a high plane”. The New York Times Magazine noted on April 15th: Another nude figure of rare quality is Memory, by Daniel Chester French. The rhythms here are slow in cadence, the figure is an image that answers to a true idea, stimulates deep reflection and soothes a disturbed spirit. This again is eloquent of Greek heritage and the power of classic art to make one forget all the madness and severity of human life.

(Photo: Memory, courtesy Postdlf, Wikimedia Commons.)

Photos: Left to right – Fourth Division Memorial, Exhibition of American Sculpture catalog; Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney with her creation, courtesy Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution; Plan for Arlington National Cemetery, courtesy Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

Also of note in the entrance court, standing directly across from one another, were Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney’s Fourth Division Memorial (a plaster casting) and Cyrus Dallin’s The Last Arrow, in bronze. The Fourth Division Memorial by Whitney (1875-1942), a dignified, pared-down portrayal of a World War I doughboy—imposing in size at 8 feet high—was designed to be the centerpiece of a memorial at Arlington National Cemetery. The project at Arlington was never built, despite Whitney receiving a payment to start, and working extensively with Thomas Hastings, the architect. It wasn’t meant to be for several reasons, not the least of which was that she was a woman. Unfortunately, even though Whitney had made a name for herself as a serious sculptor, there was still, in 1923, much ground to be covered in terms of recognizing female sculptors, and particularly female sculptors of war memorials, as equal to men. [Note: Works by women sculptors accounted for roughly 20% of the 1923 show.] The fact that Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney was a privileged member of not one, but two, famously wealthy families meant she had the means to follow her passion for art unreservedly. But it also meant that she had to overcome the stereotypic view that socialites’ pursuits were, by nature, frivolous. Whitney’s earlier Washington Heights-Inwood Memorial (above), dedicated in 1922, was her first major war memorial, and it’s one that effectively communicates the suffering of the average World War I soldier—a conscious choice on Whitney’s part not to romanticize or gloss-over the harrowing loss that comes from war. In an article titled “The ‘Useless’ Memorial”, Whitney expressed distaste for the type of memorial that had “nothing to do with what we think, feel and the way we act in every-day existence”. She advocated for war memorials to be placed on low plinths and in high-traffic areas, in order to have the most impact. The Washington Heights memorial, positioned at a busy intersection in upper Manhattan, and on a low pedestal, certainly fulfills those ideals. The Fourth Division Memorial is not nearly so wrenching, as it doesn’t directly convey anguish or loss. However, by depicting an infantry man (albeit with idealized good looks), rather than a decorated officer (as had been the standard), Whitney did at least partially answer her call for realism and everyday-human connection. It’s funny, though, that her installation design put the already-tall figure on an even taller pedestal! While it undoubtedly celebrates and (literally) elevates the average soldier, it lacks the intimacy of the earlier memorial, and, one might argue, is less successful in expressing Whitney’s message. (Photo: Washington Heights-Inwood Memorial, courtesy Beyond My Ken, Wikimedia Commons.)

Also of note in the entrance court, standing directly across from one another, were Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney’s Fourth Division Memorial (a plaster casting) and Cyrus Dallin’s The Last Arrow, in bronze. The Fourth Division Memorial by Whitney (1875-1942), a dignified, pared-down portrayal of a World War I doughboy—imposing in size at 8 feet high—was designed to be the centerpiece of a memorial at Arlington National Cemetery. The project at Arlington was never built, despite Whitney receiving a payment to start, and working extensively with Thomas Hastings, the architect. It wasn’t meant to be for several reasons, not the least of which was that she was a woman. Unfortunately, even though Whitney had made a name for herself as a serious sculptor, there was still, in 1923, much ground to be covered in terms of recognizing female sculptors, and particularly female sculptors of war memorials, as equal to men. [Note: Works by women sculptors accounted for roughly 20% of the 1923 show.] The fact that Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney was a privileged member of not one, but two, famously wealthy families meant she had the means to follow her passion for art unreservedly. But it also meant that she had to overcome the stereotypic view that socialites’ pursuits were, by nature, frivolous. Whitney’s earlier Washington Heights-Inwood Memorial (above), dedicated in 1922, was her first major war memorial, and it’s one that effectively communicates the suffering of the average World War I soldier—a conscious choice on Whitney’s part not to romanticize or gloss-over the harrowing loss that comes from war. In an article titled “The ‘Useless’ Memorial”, Whitney expressed distaste for the type of memorial that had “nothing to do with what we think, feel and the way we act in every-day existence”. She advocated for war memorials to be placed on low plinths and in high-traffic areas, in order to have the most impact. The Washington Heights memorial, positioned at a busy intersection in upper Manhattan, and on a low pedestal, certainly fulfills those ideals. The Fourth Division Memorial is not nearly so wrenching, as it doesn’t directly convey anguish or loss. However, by depicting an infantry man (albeit with idealized good looks), rather than a decorated officer (as had been the standard), Whitney did at least partially answer her call for realism and everyday-human connection. It’s funny, though, that her installation design put the already-tall figure on an even taller pedestal! While it undoubtedly celebrates and (literally) elevates the average soldier, it lacks the intimacy of the earlier memorial, and, one might argue, is less successful in expressing Whitney’s message. (Photo: Washington Heights-Inwood Memorial, courtesy Beyond My Ken, Wikimedia Commons.)

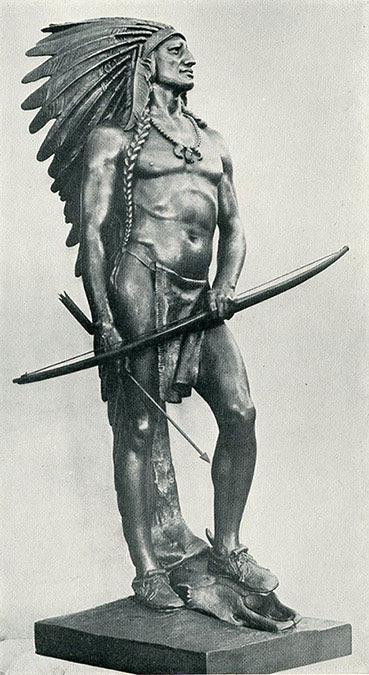

The Last Arrow (1923), also known as The Passing of the Buffalo, celebrates a warrior of a different sort. Much of Cyrus Dallin’s (1861-1944) work, including this commanding figure, reflects a childhood spent in the Utah Territory and the empathy he felt toward the indigenous people there. The 9-foot tall sculpture was in the artist’s personal collection until 1931, when it was purchased by Geraldine Rockefeller Dodge (1882-1973) to be installed at her Madison, NJ estate. After her death, it was sold to the Petty family (related to the Balls—of Ball jar fame), who moved it to Muncie, IN. There is some confusion about the date of this piece, as it’s sometimes dated 1929— even by the city of Muncie—but clearly it was sculpted by 1923 as it is pictured in the Exhibition of American Sculpture catalog. [A historian at the Cyrus E. Dallin Museum in Arlington, MA confirmed the 1923 date and said there was a second, different, version of The Last Arrow produced that year as well.] In a signed document in the collection of Minnetrista, a material culture museum in Muncie, Dallin described The Last Arrow as representing “the great tragic event in the history of the Plains Indian,” when the white men almost totally exterminated the buffalo, and he was “forced to become a pauperized ‘ward of the nation’”. The figure stands “with one foot resting upon a buffalo skull, his last arrow gone, fully conscious of his plight”. (Photo: The Last Arrow, Exhibition of American Sculpture catalog.)

The Last Arrow (1923), also known as The Passing of the Buffalo, celebrates a warrior of a different sort. Much of Cyrus Dallin’s (1861-1944) work, including this commanding figure, reflects a childhood spent in the Utah Territory and the empathy he felt toward the indigenous people there. The 9-foot tall sculpture was in the artist’s personal collection until 1931, when it was purchased by Geraldine Rockefeller Dodge (1882-1973) to be installed at her Madison, NJ estate. After her death, it was sold to the Petty family (related to the Balls—of Ball jar fame), who moved it to Muncie, IN. There is some confusion about the date of this piece, as it’s sometimes dated 1929— even by the city of Muncie—but clearly it was sculpted by 1923 as it is pictured in the Exhibition of American Sculpture catalog. [A historian at the Cyrus E. Dallin Museum in Arlington, MA confirmed the 1923 date and said there was a second, different, version of The Last Arrow produced that year as well.] In a signed document in the collection of Minnetrista, a material culture museum in Muncie, Dallin described The Last Arrow as representing “the great tragic event in the history of the Plains Indian,” when the white men almost totally exterminated the buffalo, and he was “forced to become a pauperized ‘ward of the nation’”. The figure stands “with one foot resting upon a buffalo skull, his last arrow gone, fully conscious of his plight”. (Photo: The Last Arrow, Exhibition of American Sculpture catalog.)

Photos: Left – Archival photo showing the terrace with the Soldiers pylon in the foreground, The American Architect and Architectural Review. Right – The Civil War Soldiers and Sailors Memorial pylons in their current location. Soldier pylon photo, courtesy Beyond My Ken, Wikimedia Commons. Sailor pylon photo, courtesy Daderot [Public Domain] Wikimedia Commons.

Memorial sculptures, including those of Whitney and Dallin, amounted to a substantial portion of the 1923 exhibition. This made sense, since memorials made up the majority of commissions at the time. At the show, there were a great number of war memorials, of course, along with cemetery monuments and memorials to historical figures. Most of the largest were displayed on the main terrace at the Audubon campus—an expansive space that was one flight up from the entrance court. It boggles the mind to think how hard the rigging crew must have worked to install some of these pieces on these terraces! Consider Herman MacNeil’s Civil War Soldiers and Sailors Memorial (1921), commissioned by the city of Philadelphia, and now seen on Benjamin Franklin Parkway in that city. Each of the two pylons, one devoted to soldiers, and the other to sailors, was carved of marble and measured forty feet high. We know from committee meeting minutes that they built ramps to accommodate the rigging equipment—but, still, what an exceptional feat it was to install pieces of this size, and all for a temporary show. Works of this heft echoed that aspect of permanence that Ferruccio Vitale had achieved so handily with his placement of mature trees and the like, and it made sense that MacNeil, who was serving as National Sculpture Society President at that time, would have been one of the sculptors to assume that mantle. MacNeil’s memorial, one of many entries by the artist, made the case that art, generally, and sculpture, specifically, had the capacity to inspire, lift hearts, and unify. At the top of the pylons are inscribed two important messages: the first, “One Country, One Constitution, One Destiny”, and the second, “In Giving Freedom to the Slave, We Assure Freedom to the Free”.

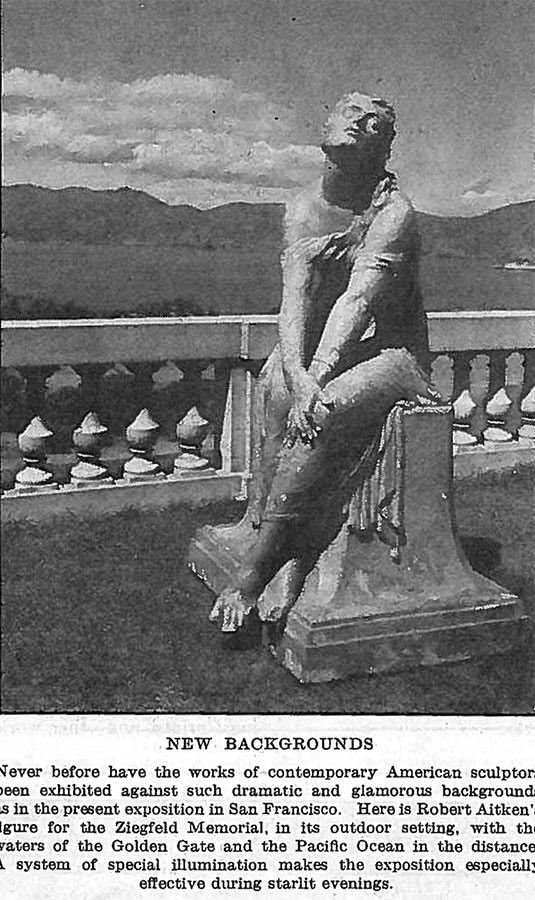

MacNeil’s memorial pylons weren’t the only monumental works on view on the main terrace. Indeed, many of the 61 pieces on the terrace were quite grand in size. Augustus Lukeman (1872-1935) showed two greater-than-life-size equestrian groups at the east end of the terrace. Robert Aitken (1878-1949), a former president of the National Sculpture Society, exhibited two works: a sober war memorial titled Comrades in Arms, and a bas-relief section from his colossal Camp Merritt Memorial, a monument to the soldiers who passed through Camp Merritt, in New Jersey, on their way to fight in World War I. Elisabeth Cary reported in The New York Times on April 13th that the Camp Merritt Memorial “looks to be in red marble, but it is not. Yesterday it was in fresh paint, as one too curious woman who put her gloved hand upon it discovered”! [This observation leads one to think that the piece on display at the show was a casting of some sort, as they wouldn’t have painted the granite of the actual bas-relief. The completed monument was dedicated in Cresskill, NJ in 1924.] (Photo: Camp Merritt Memorial, courtesy Beyond My Ken, Wikimedia Commons.)

MacNeil’s memorial pylons weren’t the only monumental works on view on the main terrace. Indeed, many of the 61 pieces on the terrace were quite grand in size. Augustus Lukeman (1872-1935) showed two greater-than-life-size equestrian groups at the east end of the terrace. Robert Aitken (1878-1949), a former president of the National Sculpture Society, exhibited two works: a sober war memorial titled Comrades in Arms, and a bas-relief section from his colossal Camp Merritt Memorial, a monument to the soldiers who passed through Camp Merritt, in New Jersey, on their way to fight in World War I. Elisabeth Cary reported in The New York Times on April 13th that the Camp Merritt Memorial “looks to be in red marble, but it is not. Yesterday it was in fresh paint, as one too curious woman who put her gloved hand upon it discovered”! [This observation leads one to think that the piece on display at the show was a casting of some sort, as they wouldn’t have painted the granite of the actual bas-relief. The completed monument was dedicated in Cresskill, NJ in 1924.] (Photo: Camp Merritt Memorial, courtesy Beyond My Ken, Wikimedia Commons.)

Two flights of stairs down from the main terrace was the “plaisance” and, beyond that, the garden. This was the part of the show that was truly a revelation, for it allowed visitors to experience sculpture in a garden setting. The Old and Middle French term “plaisance” refers to a pleasure ground—usually adjacent to a country house and always laid out with trees, flowering plants, shady pathways and garden ornament. At the exhibition, the plaisance was a park-like space, with whimsical surprises placed behind a screen of cedar trees and along the garden’s winding path.

Since photographs of the exhibition are either blurry (as they’re newspaper images) or taken at such a distance that they’re effectively illegible, it’s a happy circumstance that contemporary writers were as descriptive as they were. In the few black and white photos accompanying their articles, we can see the large cedars at the end of the plaisance lawn, for example, and the mounds of shrubs, and we can almost make out that rustic, hidden path just beyond the cedars. But to fully visualize the lush setting, we must rely on critics’ written accounts. Thank goodness they do not disappoint! Margaret Breuning, the New York Evening Post reporter, was particularly evocative:

Since photographs of the exhibition are either blurry (as they’re newspaper images) or taken at such a distance that they’re effectively illegible, it’s a happy circumstance that contemporary writers were as descriptive as they were. In the few black and white photos accompanying their articles, we can see the large cedars at the end of the plaisance lawn, for example, and the mounds of shrubs, and we can almost make out that rustic, hidden path just beyond the cedars. But to fully visualize the lush setting, we must rely on critics’ written accounts. Thank goodness they do not disappoint! Margaret Breuning, the New York Evening Post reporter, was particularly evocative:

The garden on a lower level from the main terrace is a triumph, for its leafy walks and flowery depths are alluring in themselves in this lavish bourgeoning, but there is the added fascination of finding most of the sylvan gods of legend here gleaming out from leafy thickets or playing alluring pipes to cast a spell over the prosaic world. There are all sorts of carved creatures in marble and bronze alive and watchful, great lions, frisking young goats, geese that struggle with their captors, bears at play, swift gazelles and swans. They all belong here completely, these wild things and their companion nymphs and satyrs, their great god Pan and stately Diana.

(Photo: The Plaisance. The American Architect and Architectural Review.)

Photos: Left – Archival photo showing the terrace with the Soldiers pylon in the foreground, The American Architect and Architectural Review. Right – The Civil War Soldiers and Sailors Memorial pylons in their current location. Soldier pylon photo, courtesy Beyond My Ken, Wikimedia Commons. Sailor pylon photo, courtesy Daderot [Public Domain] Wikimedia Commons.

Whereas the main terrace was replete with stately, and formal, memorial statuary, the plaisance and garden were primarily populated with more fanciful offerings, including The Spirit of the Sea (or, Sea Goddess) by Albert Henry Atkins (1899-1951), a Goose Boy by Emilio Angela (1889-1970) and the most appealing and grand Polar Bears by Frederick Roth (1872-1944). Joy of Life, a fountain by Leonard Craske (1880-1950) was nestled among some suitably-messy plants in the hidden garden, while Frederick MacMonnies’ reddish-brown marble Venus and Adonis held court in the center of the plaisance lawn. Ernest Stevens Leland, a writer for Park and Cemetery, said in the August 1923 issue of the journal, that Craske’s Joy of Life was one of several works that showed “to what extent the garden is destined to influence plastic art in this country”.

MacMonnies’ Venus and Adonis was originally created in bronze, in a diminutive size (the marble was life-size). In 1903, Lorado Taft (1860-1936), a sculptor and member of the selection committee for the 1923 show, wrote in The History of American Sculpture:

One recalls but a single work of his translated into the marble, the Venus and Adonis, and for this the sculptor perversely chose a red granulated stone full of streaks and blemishes…At any rate it is evident that with all his industry Mr. MacMonnies has little love for the painful process of the pointing instrument, the mallet, and chisel. His art is a joyous one, which must find playful and swift expression. He delights in the ‘feel’ of the clay and handles it like a magician, astonishing even himself with the results. And when the effect is obtained, when his dream is realized, then he is done with it. It must be preserved exactly as his fingers have left it. He knows that no other hand could reproduce his touch in marble. He would chafe under the restraint of doing it himself, and, besides, he has something else to do; he is already aflame with a new idea.

Taft had first seen the marble Venus and Adonis at the Paris Exposition in 1900 and had remarked, in a review for Brush and Pencil in August of that year, that the red marble version did “not seem to be altogether a success”. Indeed, in comparison to the bronze, the marble does come across as clunky—especially considering how much of the stone is left uncarved. Still, it was generally well-received by attendees who wrote about the 1923 show. The New York Herald remarked on April 13th that “Mr. MacMonnies’ Venus and Adonis has been lent by the Brooklyn Museum and will surprise many, as it is little known. It is carved in reddish marble and is somewhat archaistic in style, dating from his early period”. (Photos: Left – Venus and Adonis, Exhibition of American Sculpture catalog; right – The Paris Exposition, Venus and Adonis is the dark group in the foreground directly in front of the raised equestrian statue.)

Taft had first seen the marble Venus and Adonis at the Paris Exposition in 1900 and had remarked, in a review for Brush and Pencil in August of that year, that the red marble version did “not seem to be altogether a success”. Indeed, in comparison to the bronze, the marble does come across as clunky—especially considering how much of the stone is left uncarved. Still, it was generally well-received by attendees who wrote about the 1923 show. The New York Herald remarked on April 13th that “Mr. MacMonnies’ Venus and Adonis has been lent by the Brooklyn Museum and will surprise many, as it is little known. It is carved in reddish marble and is somewhat archaistic in style, dating from his early period”. (Photos: Left – Venus and Adonis, Exhibition of American Sculpture catalog; right – The Paris Exposition, Venus and Adonis is the dark group in the foreground directly in front of the raised equestrian statue.)

In the eyes of most critics, the garden and plaisance made a favorable impression. Elisabeth Cary, of The New York Times, noted on April 13th that “all through the plaisance and the secluded garden to the west there are charming things that could never be as lovely anywhere except in a garden…this will be a fairy story place for children”. Nevertheless, there were some reports that weren’t quite as glowing. Royal Cortissoz, of the New York Tribune, for one, in his April 22nd review, managed to slight the accomplishments of American sculptors about as much as he praised them. Still, his take was generally upbeat, however much he questioned the capacity of American artists to find their voice and purpose, and he certainly didn’t deny the appeal of the garden spaces. Whatever flaws existed in Cortissoz’s view, there was “nothing to mar the seriousness and beauty of this episode in our art history”.

The more pointed critique of the exhibition overall was published in The New York Times Magazine on June 24th, after the show had been open awhile and some of the novelty had, perhaps, worn off. Frustratingly, the article lacks a byline, so it can’t be assigned to any particular critic. In this prickly review, we learn that, by the end of June, “the exhibition up at the Hispanic Museum [had] ripened as much as it [would]”, as the “first batch of green trees and shrubs [had] been replaced by the second batch”. The author gives the organizers credit for trying, as it was the first attempt at assembling such a mass of objects. And the critic understood that the public would look past some of the obvious failures, since “there is nothing our public loves so well as a first time”. Unfortunately, the writer found that:

Problems of color and scale seem to have proved insoluble in arranging the entrance court and the main terrace. The symmetry achieved with the different objects, large and small, is the kind to be appreciated best from a low-flying airplane or on a diagram; it is difficult to grasp it as you approach. And even when you become conscious that one thing does balance another, that a green satyr on one side is echoed by a green nymph on the other; that a marble head on one side chimes with a stone head on the other, your eye takes in only with difficulty more than one side at a time, and thus sees a disturbing progression of big things and little, dark and light, with no real harmony.

The author also found fault with the “cheap…vulgar wood pedestals”, which had been too-quickly built to order, and with the way the “stiff little niches” were inelegantly arranged. Whereas most critics lauded the speed with which the exhibition had come together, this critic bemoaned the haphazardness that came with organizing on the fly. However, when it came to the plaisance and garden, there was no shortage of praise, for “in this lovely region…sea nymphs, birds, beasts and babies…are subdued to one deep impression of homogeneous beauty, in which evergreens and daisies, ageratum and unbroken greensward fulfill their individual parts to the benefit of the whole”.

Of the nearly 800 works that were shown at the 1923 exhibition, only 141 were presented outdoors—so the bulk of the show was displayed in the buildings of the Hispanic Society, the Academy of Arts and Letters, and the Numismatic Society (all at the Audubon Terrace campus). The sheer number of pieces makes it impossible to cover it all here, but suffice to say that the rooms were full-to-bursting with small-to-medium sized sculptures. The exhibition also included a great number of medals, and a few rooms devoted to drawings and photographs of pieces too large to install at the show. The landscape architects brought the outside in to a certain extent, hanging swags of greenery and positioning plants to set off the works to their best effect. Luckily the exhibition catalogue came with a handy pamphlet that listed all the pieces by room/area, though it lacks details on material, date, and size, making it hard to judge scale, and at times making it impossible to tell whether it was the actual marble statue on view, or a plaster replica. Clearly the organizers did not take into account the needs of historians and researchers in the year 2019! (Photos: American Architect and Architectural Review.)

Of the nearly 800 works that were shown at the 1923 exhibition, only 141 were presented outdoors—so the bulk of the show was displayed in the buildings of the Hispanic Society, the Academy of Arts and Letters, and the Numismatic Society (all at the Audubon Terrace campus). The sheer number of pieces makes it impossible to cover it all here, but suffice to say that the rooms were full-to-bursting with small-to-medium sized sculptures. The exhibition also included a great number of medals, and a few rooms devoted to drawings and photographs of pieces too large to install at the show. The landscape architects brought the outside in to a certain extent, hanging swags of greenery and positioning plants to set off the works to their best effect. Luckily the exhibition catalogue came with a handy pamphlet that listed all the pieces by room/area, though it lacks details on material, date, and size, making it hard to judge scale, and at times making it impossible to tell whether it was the actual marble statue on view, or a plaster replica. Clearly the organizers did not take into account the needs of historians and researchers in the year 2019! (Photos: American Architect and Architectural Review.)

The most potent takeaway from the caustic June 24th review was a hopeful one: that the exhibition was a decent start, from which great things could come. The writer remarks, “It is impossible not to think that, with something more of cooperation and foresight, a somewhat more extensive and detailed preliminary planning, the whole could have been made greater than any of its parts”. Not surprisingly, the organizers of the show decided to capitalize on their blockbuster achievement—and why shouldn’t they have? The National Sculpture Society harnessed all the momentum of the 1923 show and embarked on planning a second exhibition. The next show would be held in San Francisco, and it would be even larger in scope—in fact nearly twice as large, with nearly 1,400 sculptures. It took six years for it to happen, but it did finally open on April 27, 1929 at the Palace of the Legion of Honor. Unlike the 1923 exhibition, which was positively received (mostly) by critics and public alike, the 1929 show was almost universally panned. There were many factors for this, but the most important, posited by art historian Jennifer Jane Marshall in her excellent 2015 analysis, was the size. It was just too big, and because it was, it reinforced societal worries about mass production, and overproduction. [Please see Ms. Marshall’s fascinating paper on the subject: http://scalar.usc.edu/works/the-space-between-literature-and-culture-1914-1945/vol11_2015_marshall.]

Unfortunately for us, there would never again be an American sculpture exhibition to rival the size and scope of the 1923 show and its 1929 sequel. Elizabeth Helm, currently an archivist at the National Sculpture Society, when asked about why there weren’t subsequent shows of that size, remarked that after the 1929 show, the NSS decided it was better to focus on single-artist or small-group exhibitions. The disagreeable press coverage during the 1929 show, combined with the stock market crash later that year, did not lay the groundwork for further exhibitions, shall we say. The cost alone was insurmountable, especially without a great benefactor like Archer Huntington footing the bill. Consequently, these two exhibitions—groundbreaking in every sense of the word—are now basically forgotten.

Unfortunately for us, there would never again be an American sculpture exhibition to rival the size and scope of the 1923 show and its 1929 sequel. Elizabeth Helm, currently an archivist at the National Sculpture Society, when asked about why there weren’t subsequent shows of that size, remarked that after the 1929 show, the NSS decided it was better to focus on single-artist or small-group exhibitions. The disagreeable press coverage during the 1929 show, combined with the stock market crash later that year, did not lay the groundwork for further exhibitions, shall we say. The cost alone was insurmountable, especially without a great benefactor like Archer Huntington footing the bill. Consequently, these two exhibitions—groundbreaking in every sense of the word—are now basically forgotten.

Yet, it does seem that, for a few shining months in 1923, the National Sculpture Society accomplished its goals. It set out to put a spotlight on sculpture and it did that. In a May 1918 article in Current Opinion, the editor, Edward J. Wheeler, in reviewing an essay in the Yale Review by art critic Arthur Kingsley Porter (1883-presumed 1933), emphasized the necessity of educating the American public about art. Wheeler, echoing Porter’s sentiments, felt that “strong forces are arrayed against the appreciation of art in America. There is a campaign against intellectuality, against beauty, being waged throughout the land”. Both men saw consumerism and materialism, and the commercialism associated with advertising as corrupting influences—and both saw the need to fight those forces tooth and nail. “The fact that the majority of the people in these United States have no comprehension of beauty,” wrote Wheeler, “is the reason that ugliness surrounds us on all sides”. (Photos: Above and right – “American Sculpture Seeks New Horizons“, Literary Digest 101, May 11, 1929.)

Yet, it does seem that, for a few shining months in 1923, the National Sculpture Society accomplished its goals. It set out to put a spotlight on sculpture and it did that. In a May 1918 article in Current Opinion, the editor, Edward J. Wheeler, in reviewing an essay in the Yale Review by art critic Arthur Kingsley Porter (1883-presumed 1933), emphasized the necessity of educating the American public about art. Wheeler, echoing Porter’s sentiments, felt that “strong forces are arrayed against the appreciation of art in America. There is a campaign against intellectuality, against beauty, being waged throughout the land”. Both men saw consumerism and materialism, and the commercialism associated with advertising as corrupting influences—and both saw the need to fight those forces tooth and nail. “The fact that the majority of the people in these United States have no comprehension of beauty,” wrote Wheeler, “is the reason that ugliness surrounds us on all sides”. (Photos: Above and right – “American Sculpture Seeks New Horizons“, Literary Digest 101, May 11, 1929.)

This desire to educate and inspire the public was, of course, what drove the organizing committee to plan the 1923 show. After all, promoting awareness and improving appreciation would lead to more commissions for artists. The April 15th review in the New York Times Magazine laid out the challenges of elevating sculpture in the eyes of the public, and concluded that the organizers, on the whole, had accomplished their goals quite admirably:

Nothing is so quickly forgotten by the public as the sculpture in their parks and on their buildings. When they are near it they cannot see it; when they are far enough away from it to see it they are looking at something else. Thus an American sculpture has grown up only too literally under our eyes without our awareness. The present exhibition will help us to see how admirable it is, how various, how full of character and significance.

The 1923 show would indeed do that; it would help Americans, or at least New Yorkers, to really see the art around them. But the 1929 exhibition that followed taught the organizers something equally important: that when it came to imparting knowledge—especially when dealing with a fickle, judgmental, and variably astute audience—less was most certainly more.

Many thanks to Jennifer Wingate, author of Sculpting Doughboys: Memory, Gender, and Taste in America’s World War I Memorials, (Surry: Ashgate Publishing Limited), 2013, for her assistance.

Thanks to the docents at the Cyrus Dallin Museum in Arlington, MA, for their gracious help.

Thanks also to Karen Vincent at Minnetrista in Muncie, IN, for her kindness.