The Magical Appeal of Blairsden

By Barbara Israel

Growing up in the shadow of an extraordinary property is a childhood delight, an experience to which many can attest. In my case, it was Blairsden, a magnificent Louis XIII-style chateau designed by Carrère and Hastings, for Clinton Ledyard Blair (1867-1949). [Photo: Mick Hales]

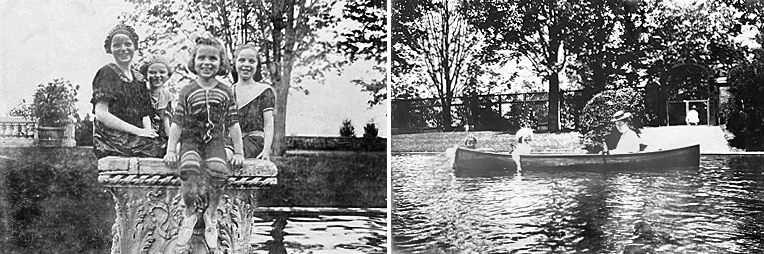

Located on top of a huge hill in the center of hundreds of acres of woodland and farmland in Peapack-Gladstone, NJ it was less than a mile from our house. My sister, Susan, and I were drawn in like bees to honey by a pair of grand iron entrance gates flanked by a classical wall fountain. We wandered curiously up a mile long driveway that culminated in a sudden view of a huge stone house on a steep hill with fountains and water cascades stretching all the way down the hill, almost to where we were standing.

We gingerly crept around, making our way to the side of the house, keeping a safe distance from any watchful eyes. Someone had told us at that time that the house was owned by the Sisters of St. John the Baptist, so we weren’t afraid of much more than an admonishment. As we reached

the edge of the entrance drive, we were transfixed by the sight of a 300-foot long, reflecting pool with tranquil waters, mirroring the beauty of the mansion. Large trees edged the pool, adding to the visual impact of the entrance. Had we only known that this same reflecting pool had once provided the opportunity for Mr. Blair’s four daughters to paddle a canoe around in the middle of this luxurious feature. [Photos, top: Mick Hales; bottom: loaned by Barry Thomson]

Next, we encountered, along the left side of the drive, a daunting collection of 9-foot-high marble busts of the first twelve Roman emperors placed on columns. We had no idea who they were or why they were there, just that they were stern and unsmiling, showcasing their own unique features and characteristics. I remember thinking “what are they doing there?” Later, I found out that they reflected Mr. Blair’s, appreciation for the classical world and its enduring influence on art and culture. The Roman emperors were powerful figures who shaped the course of history, and their busts symbolize strength, leadership, and the pursuit of greatness.

I had no idea at the time that later, I would come to understand and appreciate the use of such ornaments in the decoration of gardens. The history of these marble busts is as intriguing as the property itself. According to the Blair family’s oral tradition the busts were acquired by Mr. Blair from the French government. It is believed that he imported them in the hold of his 254 ft. steam yacht, the “Diana”, possibly to save on shipping costs and to avoid one of his pet peeves, punitive customs duties. I haven’t found a photo of the “Diana”, but fortunately while visiting Blairsden in 2014 when it was the site of Mansion in May, I came across a playing card from the “Diana” bearing a color illustration of the yacht with Mr. Blair’s monogram. The pennant on the right is that of the New York Yacht club of which Mr. Blair was elected Commodore in 1910. How and if he had an introduction to a such an elite collection, that might well have once belonged to Napoleon, has fascinated and stumped historians for years. We do know that he worked with the infamous Lord Joseph Duveen (1869-1939) in later years while furnishing his New York City mansion. Beyond that possibility, among others, no one has discovered who might have brokered a deal (if true) between Mr. Blair and the French government. I’ll leave that question to future researchers to track down! [Photos: left, Mick Hales; right, Barry Thomson]

Blairsden had been built between 1898 and 1903. After Mr. Blair died in 1949 it was sold to the Sisters of St. John the Baptist who oversaw it for many years as a women’s retreat. In 2002 they parted with it and since then it has been owned by various entities. Currently, it is privately owned by 30 Blair PG and is being beautifully and carefully restored and preserved. Recently, I was treated to a tour of the outdoors and can attest to that! Our guide, historian Barry Thomson, reminded us that no expense had been spared when it was built. Before construction began, they sliced 15 feet off the top of the hill in order to place the house on a level and more desirable spot. A special funicular was installed to haul heavy objects up the massive hill. Furthermore, 100 trees

were dragged up by teams of horses over the course of many months. James Leal Greenleaf (1857-1933) was their landscape architect who was known as one of the first to successfully transplant full grown trees. Thomas Hastings, Carrère’s design partner, installed a multitude of formal gardens. Luckily, Ledyard Blair and his family had a thriving investment banking business and his grandfather, John Insley Blair (as in Blairstown NJ and Blair Academy) had left his heirs in very good shape. [Photo: Barbara Israel]

My sister and I were some of the lucky ones who experienced this house and property as children and can admit to its having had a profound effect on us over the years. In my 1999 book, Antique Garden Ornament: Two Centuries of American Taste Blairsden is featured in my introduction. I had asked the Sisters early on if we could come and take photographs for the book but they hadn’t been able to give me the go ahead. At last, one day in the Spring, they said “Come now, the dogwoods are out.” And off we went with all my employees and Mick Hales, my photographer, to see this spectacular property. What a day that was. Some of the pictures illustrated here were taken that very day.

Many other people have mentioned to me that they too have felt the same significant draw over many years to visit and research its fascinating history. Not only historians like Barry Thomson and Mac Griswold, but also many others like myself and even Mr. Blair’s own relatives. The day of the tour I met his great-granddaughter who grew up nearby and became a landscape architect. We all hope to continue going back to Blairsden to once again enjoy the magical, sweeping views from the terraces and gardens created by Gilded Age architects to captivate visitors with the grandeur and elegance of a bygone era.

An Enchanting Trip to Seville

By Eva Schwartz

Ever since my husband and I traveled to Spain in 2002, we’d intended to return. But life often gets in the way of the best laid plans, so twenty-one years ticked by before we finally made it back. This past summer, we spent seventeen days there, including four days in Seville, one of the cities we’d missed on our first visit. I was thrilled to finally be getting to Andalusia, but I was more than a little worried about how punishing the heat might be in the middle of July! In truth, my concern was well-warranted – temperatures hovered around 110 degrees Fahrenheit every day – but what I hadn’t counted on was the many ways in which Seville does its very best to keep you cool: there’s the classic afternoon siesta when the city shuts down and you’ve nothing better to do than relax indoors, the large coolers of chilled orange and lemon water placed prominently just inside our hotel lobby, the wide-brimmed hats, fans, and parasols sold on every corner, not to mention the misting machines placed in the most opportune locations. What’s more, Seville’s heat cultivates a relaxed, easy-breezy, come-what-may sensibility. No one’s rushing in Seville, and it rubs off on even the most fast-walking New Yorker (ahem). [All photos: Eva Schwartz, unless noted]

Left: Lion’s Gate entrance to Real Alcazár. Right: The crenellated wall in the mid-ground of the view from the Cathedral delineates Real Alcázar.

There’s lots to see and do in this gorgeous place, where a casual stroll will have you photographing practically every building (as I did) because each one charms more than the last. We did a rooftop tour of the 15th-century Cathedral of Seville, which was one of the great experiences of my life – notwithstanding the many narrow, winding staircases and 105-degree temps! But my favorite spot was right across the plaza from the cathedral – the truly jaw-dropping Real Alcázar, the royal palace of Seville. It’s a sprawling site in terms of size, but it’s just as expansive with regard to architectural heritage; it was built and rebuilt over centuries, so it incorporates design influences ranging from Moorish to Gothic, Baroque to Renaissance classical, Mannerist to 19th-century Romantic. The gardens alone are a mind-boggling array of outdoor rooms, of which I only saw about half.

We had booked tickets in advance, which turned out to be hugely helpful in allowing us to bypass a portion of the crowd. We entered at the Lion’s Gate, the main entrance that was once called the Hunting Gate, later renamed for the tiled lion plaque above the arched doorway. The plaque – a fairly recent addition, installed in 1894 in commemoration of the 1248 conquest of Seville by Christian King Ferdinand III (1199-1252) – depicts a crowned lion holding a cross aloft, and includes the Latin inscription, “’AD UTRUMQUE”, translated “ready to do what is necessary”. Ironically, this tribute to Christian rule is installed on one of the oldest and most robust Moorish walls of the palace, built in the 11th century by a Muslim emperor of the Almohad dynasty.

We had booked tickets in advance, which turned out to be hugely helpful in allowing us to bypass a portion of the crowd. We entered at the Lion’s Gate, the main entrance that was once called the Hunting Gate, later renamed for the tiled lion plaque above the arched doorway. The plaque – a fairly recent addition, installed in 1894 in commemoration of the 1248 conquest of Seville by Christian King Ferdinand III (1199-1252) – depicts a crowned lion holding a cross aloft, and includes the Latin inscription, “’AD UTRUMQUE”, translated “ready to do what is necessary”. Ironically, this tribute to Christian rule is installed on one of the oldest and most robust Moorish walls of the palace, built in the 11th century by a Muslim emperor of the Almohad dynasty.

From the Lion’s Gate, we progressed through a small courtyard and then through another arched doorway into what’s known as the Hunting Courtyard. This large space, used historically as a gathering place for the royal hunting party, is beautifully appointed along one side with a classical arcaded portico, added in 1504 to accommodate the newly conceived House of Commerce. However, my eye was most drawn to a somewhat forgotten corner of the courtyard, where a stunning marble pedestal seemed to be casually placed. I assumed it to be Roman, though I was never able to determine how it came to be at the palace. Ornamented with a delicate vegetal border and acanthus scrollwork, the pedestal likely held a statue in its day, perhaps of Curtus Balbinus, the gentleman referred to in the lengthy (and, to me, mysterious) Latin description carved on one of its faces.

From the Lion’s Gate, we progressed through a small courtyard and then through another arched doorway into what’s known as the Hunting Courtyard. This large space, used historically as a gathering place for the royal hunting party, is beautifully appointed along one side with a classical arcaded portico, added in 1504 to accommodate the newly conceived House of Commerce. However, my eye was most drawn to a somewhat forgotten corner of the courtyard, where a stunning marble pedestal seemed to be casually placed. I assumed it to be Roman, though I was never able to determine how it came to be at the palace. Ornamented with a delicate vegetal border and acanthus scrollwork, the pedestal likely held a statue in its day, perhaps of Curtus Balbinus, the gentleman referred to in the lengthy (and, to me, mysterious) Latin description carved on one of its faces.

The courtyard is otherwise dominated by the monumental entrance façade of Peter I’s palace. From about 1360 to about 1366, Peter I (1334-1369), king of Castile from 1350 to 1369, built a palace for himself by renovating and expanding a portion of the Real Alcázar. Although the Muslim rulers of Seville had been conquered in 1248, Muslim citizens of the region, called Mudéjar, were not driven out. Neither were they forced into Christianity – at least not for a long while – so long as they declared allegiance to the Christian crown. [Indeed, the Mudéjar were permitted to worship as Muslims until the punishing laws of the Spanish Inquisition were imposed in the late 15th century.] Peter I, having an abiding admiration for Moorish art and architecture, hired Mudéjar artists and craftsmen from Seville, Toledo, and Granada to create the luxurious rooms of the palace, all incorporating both Islamic and Byzantine (Christian) design motifs. The resultant style, an amalgamation of Moorish design elements adapted to the tastes of Christian rulers, is called “Mudéjar” in honor of the Muslim artisans who stayed and worked in the region. The palace of Peter I survives as one of the finest examples of Mudéjar architecture in Spain.

The courtyard is otherwise dominated by the monumental entrance façade of Peter I’s palace. From about 1360 to about 1366, Peter I (1334-1369), king of Castile from 1350 to 1369, built a palace for himself by renovating and expanding a portion of the Real Alcázar. Although the Muslim rulers of Seville had been conquered in 1248, Muslim citizens of the region, called Mudéjar, were not driven out. Neither were they forced into Christianity – at least not for a long while – so long as they declared allegiance to the Christian crown. [Indeed, the Mudéjar were permitted to worship as Muslims until the punishing laws of the Spanish Inquisition were imposed in the late 15th century.] Peter I, having an abiding admiration for Moorish art and architecture, hired Mudéjar artists and craftsmen from Seville, Toledo, and Granada to create the luxurious rooms of the palace, all incorporating both Islamic and Byzantine (Christian) design motifs. The resultant style, an amalgamation of Moorish design elements adapted to the tastes of Christian rulers, is called “Mudéjar” in honor of the Muslim artisans who stayed and worked in the region. The palace of Peter I survives as one of the finest examples of Mudéjar architecture in Spain.

The interior architectural spaces at the palace are truly extraordinary, especially in the use of intricate, interlaced arabesque ornament (a marvel of Moorish design). I could have spent hours wandering the seemingly endless assortment of rooms. In truth, I stumbled upon several by sheer luck, after taking a few fateful turns in pursuit of one destination or another. Peter I’s palace is an absolute masterpiece – but also a rather confounding labyrinth!

When I emerged from the palace interior, I found myself in the gardens – and was immediately entranced by the sight. The gardens of the Real Alcázar feature over 20,000 plants, encompassing over 187 distinct species – a mind-blowing assortment to behold. The oldest gardens – built by Moorish rulers and Christian kings in the Mudéjar style – have all the markers of iconic Moorish design. Trees and plants are laid out in regular geometric arrangements. There is a profusion of pools, low-lying fountains, and other water features, bringing movement, melody, and an aspect of refreshment to the space. There are scented flowers and aromatics and the complete effect is a most welcome assault on the senses.

I began my tour with the enchanting Garden of the Flowers, a walled garden created by King Philip II (1527-1598) upon what was once a livestock pen. Philip II had a great interest in botany and was a veritable flower connoisseur. Under his influence, Gregorio de los Ríos, a chaplain and gardener in Philip II’s employ, published the first Spanish treatise on ornamental flora, titled Agricultura de Jardines (1592). Both men considered flowers to be manifestations of Divine beauty.

The major focal piece of the Garden of the Flowers is a Mannerist-style architectural niche featuring a bust of Phillip II’s father, Charles V (1500-1558), carved in the manner of ancient Rome. On the opposing wall, a built-in bench with delightful 16th-century blue and white tiles is a reminder that Seville was, historically, the epicenter of Spanish tile making. The garden itself is laid out in four sections with a low fountain at the center, reflecting the Moorish design influence still prevalent in the 16th century. Each quadrant is filled with topiary-form bitter citrus trees, yet another holdover from Islamic garden design. When initially planted, the garden was reportedly filled with 174 citrus trees, but there are far fewer in evidence today. And, of course, in keeping with Philip II’s taste, the original garden was also bursting with varieties of flowers. I noticed several climbing roses along the garden walls, but sadly nothing was in flower when I visited. I can only imagine how sublime the orange blossoms must be in the spring! In the absence of any blooms, my attention was captured by a peacock perched high atop the garden wall, his plumage an elegant cascade.

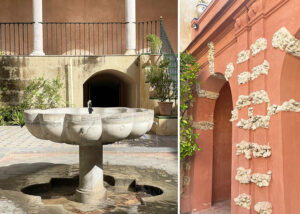

Winding my way through the gardens closest to the palace buildings, I stopped for a few minutes in the so-called Troy Garden, where I admired a simple marble fountain installed at the center of a sun-filled courtyard. I loved the mini lion’s-head spouts, and the way the pool mimicked the traditional Moorish shape of the fountain bowl. I found out later that the fountain is likely dated to the 10th century, one of the oldest extant garden ornaments on the property. The courtyard is enclosed on one side by an arcaded portico, a 17th-century repurposing of a much older Islamic wall. It was modified/reconstructed by the Italian-born architect, Vermondo Resta (ca. 1555-1625), who worked in the late Mannerist and Baroque styles. The terra-cotta-colored portico includes sections of rough natural stone – a nod to the wider European fashion for grottoes and rusticated ornament in the 16th and 17th centuries (and beyond!). It’s one of many grotto-like features of the palace gardens.

Winding my way through the gardens closest to the palace buildings, I stopped for a few minutes in the so-called Troy Garden, where I admired a simple marble fountain installed at the center of a sun-filled courtyard. I loved the mini lion’s-head spouts, and the way the pool mimicked the traditional Moorish shape of the fountain bowl. I found out later that the fountain is likely dated to the 10th century, one of the oldest extant garden ornaments on the property. The courtyard is enclosed on one side by an arcaded portico, a 17th-century repurposing of a much older Islamic wall. It was modified/reconstructed by the Italian-born architect, Vermondo Resta (ca. 1555-1625), who worked in the late Mannerist and Baroque styles. The terra-cotta-colored portico includes sections of rough natural stone – a nod to the wider European fashion for grottoes and rusticated ornament in the 16th and 17th centuries (and beyond!). It’s one of many grotto-like features of the palace gardens.

Following the Troy Garden, my family and I ventured into the Dance Garden— named after two mythological dancing figures that used to stand atop columns, but no longer survive— and we were pleased to find a long tiled bench in a shady spot. There’s nothing like a well-earned respite after you’ve been on your feet in the heat! A low-lying fountain burbled in front of us, this one with a 16th-century bronze fountain spout and a hexagonal basin tiled in shades of russet, ochre and olive. Just ahead there were steps leading up to the Pond Garden, of which the largest single component is a square shaped pool, a reservoir for a Roman aqueduct that serviced the palace until about 1575 (after which the pool became solely ornamental).

Following the Troy Garden, my family and I ventured into the Dance Garden— named after two mythological dancing figures that used to stand atop columns, but no longer survive— and we were pleased to find a long tiled bench in a shady spot. There’s nothing like a well-earned respite after you’ve been on your feet in the heat! A low-lying fountain burbled in front of us, this one with a 16th-century bronze fountain spout and a hexagonal basin tiled in shades of russet, ochre and olive. Just ahead there were steps leading up to the Pond Garden, of which the largest single component is a square shaped pool, a reservoir for a Roman aqueduct that serviced the palace until about 1575 (after which the pool became solely ornamental).

The Pond Garden was undergoing restoration when we visited, so access was restricted. The view of it from where we sat in the Dance Garden, however, was just splendid; the light shimmered off every surface. I couldn’t get close enough to see the exceptional figure of Mercury at the center of the pool, nor the 17th-century frescos adorning several arched niches along one side, but I read about them later. The Mercury, completed in circa 1575, was likely modeled by Diego de Pesquera, an Andalusian sculptor active in Seville from about 1571 to 1580, and then cast in bronze by Bartolomé Morel (active 1504-1579). The figure itself is largely in keeping with many examples of Mercury I’ve seen, complete with winged helmet, winged sandals, and a caduceus, the serpent-twined winged staff that is Mercury’s most identifiable attribute. The vasiform base upon which Mercury stands, however, displays all the quirkiness of Mannerism, replete with a mélange of cherubs and grotesque figures that looks a bit comical to the modern eye. [Right: Photo by CEphoto, Uwe Aranas, via Wikimedia Commons]

The arcaded wall that includes the aforementioned frescoes is another architectural flourish achieved by Vermondo Resto. Here, he once again reworked a Moorish wall to bring it up to date, reflecting the changing tastes of the court. This wall exhibits an even more exuberant use of rusticated stonework than had been employed in the Troy Garden. It’s a dramatic effect, again echoing the fascination for grottoes that captivated architects and garden designers of the period.

After having rested a bit in the Dance Garden, I spotted a nondescript entranceway, with stairs leading to a tunnel below the main floor of the palace. Having no idea what I might find, I was gobsmacked to discover one of the most serenely beautiful and contemplative spaces on the property – a vaulted crypt with a long cistern filled with water. The baths of Lady María de Padilla, as they’re called, were built in the 12th century in the Moorish style and then adapted in the 13th century by Alfonso X (reigned 1252-1284), who added the gothic style groin vaults. Originally used to collect rainwater for drinking and for keeping foodstuffs cool, use of the cisterns shifted significantly during Peter I’s rule, as his paramour, Lady María de Padilla (1334-1361), regularly took her baths there. Legend has it that Peter I cheekily required court visitors to take a drink from Lady María’s baths before they could have an audience with him. Whatever its historical use, I was absolutely smitten with the place, especially with the way the light filtered in through tucked-away portals, and with how the gothic vaults were reflected in the cool, still cistern waters.

After having rested a bit in the Dance Garden, I spotted a nondescript entranceway, with stairs leading to a tunnel below the main floor of the palace. Having no idea what I might find, I was gobsmacked to discover one of the most serenely beautiful and contemplative spaces on the property – a vaulted crypt with a long cistern filled with water. The baths of Lady María de Padilla, as they’re called, were built in the 12th century in the Moorish style and then adapted in the 13th century by Alfonso X (reigned 1252-1284), who added the gothic style groin vaults. Originally used to collect rainwater for drinking and for keeping foodstuffs cool, use of the cisterns shifted significantly during Peter I’s rule, as his paramour, Lady María de Padilla (1334-1361), regularly took her baths there. Legend has it that Peter I cheekily required court visitors to take a drink from Lady María’s baths before they could have an audience with him. Whatever its historical use, I was absolutely smitten with the place, especially with the way the light filtered in through tucked-away portals, and with how the gothic vaults were reflected in the cool, still cistern waters.

From the baths, I passed through the Dance Garden into the much larger Ladies’ Garden, completed in the early 17th century by Vermondo Resto. It’s a vast and remarkably formal space, obviously designed to impress. I was thinking that Resto had clearly met the brief with this garden, which was supposedly to build a garden big enough that the ladies of court could stroll and talk without their conversations being heard by nosey eavesdroppers in busier areas of the palace. While in the garden, you can’t help but notice the monumentally-scaled Neptune fountain with Genoese marble dolphin spouts and a bronze figure of Neptune by Diego de Pesquera and Bartolomé Morel (the same pair who’d crafted the previously-noted figure of Mercury). The Ladies’ Garden also includes the oldest building on the palace grounds – the Pavilion of Charles V, dating to the Moorish era, but adapted by Charles V into a Renaissance-style retreat in celebration of his marriage to Princess Elizabeth of Portugal. Every inch of the pavilion walls is filled with the intricate arabesques of Moorish tile work.

Another charming feature of the Ladies’ Garden is the Lion’s Bower, a large folly-like structure with the exaggerated proportions of the Mannerist style. The building is in muted yellow and red tones with a blue-tiled domed roof. Of particular note is the playfully cartoonish lion fountain with grotesque-mask basin that spouts into a rectangular reflecting pool. At the time of its construction, the pool was fed by a well with a waterwheel, part of a complicated irrigation system that provided water to nearby orchards (sadly, no longer present).

Another charming feature of the Ladies’ Garden is the Lion’s Bower, a large folly-like structure with the exaggerated proportions of the Mannerist style. The building is in muted yellow and red tones with a blue-tiled domed roof. Of particular note is the playfully cartoonish lion fountain with grotesque-mask basin that spouts into a rectangular reflecting pool. At the time of its construction, the pool was fed by a well with a waterwheel, part of a complicated irrigation system that provided water to nearby orchards (sadly, no longer present).

At one point, I peered down one of the many boxwood-lined intersecting paths of the Ladies’ Garden and snapped  a photo to capture the glorious view. If only I had gotten closer (alas, the heat was wearing me down and the Ladies’ Garden offered little shade), I would have had the chance to experience one of the rarest garden features in Europe – a working organ fountain. The only such fountain in Spain, and one of only three of its type in Europe (and one of only four in the world), the organ fountain of the

a photo to capture the glorious view. If only I had gotten closer (alas, the heat was wearing me down and the Ladies’ Garden offered little shade), I would have had the chance to experience one of the rarest garden features in Europe – a working organ fountain. The only such fountain in Spain, and one of only three of its type in Europe (and one of only four in the world), the organ fountain of the

Ladies’ Garden is a spectacle of engineering. Every hour on the hour it plays two songs – one a religious piece dedicated to the Virgin Mary and the other a 17th-century pop tune titled “Glosa al Canto Ilano” – the musical notes generated by water pressure and air flowing through a series of pipes. The earliest organ fountain, located in the ancient Greek city of Alexandria, was created by the engineer Ctesibius in the 3rd century BC. The most famous organ fountain is no doubt the Fontana dell’Organo at the Villa d’Este in Tivoli, Italy.

Until recently the organ fountains of the world, so few in number, had all been out of working order. But in the early 2000s, Rodney Briscoe, a British fountain enthusiast with a knack for creative problem-solving, contacted the Real Alcázar, the Villa d’Este, and the Quirinale Palace (also in Italy, where another organ fountain resides) to offer his restoration services. Sure enough, Mr. Briscoe brought these historic jewels back to life – and now he’s considered the only person in the world who can fix them if they break down!

Towards the end of the day, I stumbled upon an enormous grotto-style mound, termed the “old cave”, in the Garden of the Cross. This curious feature is the last remnant of an ancient-style labyrinth, no longer extant, that used to terminate at this very mound— a representation of Mount Parnassus in Greece. The greater labyrinth was destroyed at the behest of María Cristina of Austria (1858-1929), Queen of Spain and the second wife to Alfonso XIII (1886-1941), because, amusingly, the ladies and gentlemen of the court were too often getting lost in it. The mound itself is dripping with all the character that you might expect from a planted grotto feature, and it makes sense aesthetically speaking, considering the other rusticated components of the gardens. I read that it’s one of the most biodiverse spots on the grounds, with plants representing all the continents of the globe.

Towards the end of the day, I stumbled upon an enormous grotto-style mound, termed the “old cave”, in the Garden of the Cross. This curious feature is the last remnant of an ancient-style labyrinth, no longer extant, that used to terminate at this very mound— a representation of Mount Parnassus in Greece. The greater labyrinth was destroyed at the behest of María Cristina of Austria (1858-1929), Queen of Spain and the second wife to Alfonso XIII (1886-1941), because, amusingly, the ladies and gentlemen of the court were too often getting lost in it. The mound itself is dripping with all the character that you might expect from a planted grotto feature, and it makes sense aesthetically speaking, considering the other rusticated components of the gardens. I read that it’s one of the most biodiverse spots on the grounds, with plants representing all the continents of the globe.

There’s a new labyrinth on the property comprised of cypresses, arborvitaes, and myrtles, built in 1914 to replace the one so unceremoniously razed by Queen María Cristina. However, allow me to caution you, dear reader – my family and I spent a good twenty minutes trapped in this maze, trying in vain to make our way to the exit. It was a hilariously frustrating end to a perfect day at a most exceptional place. Make the trip – you won’t regret it! [Photo: Azukik, CC-BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons]