A Research Reminiscence

By Barbara Israel

Occasionally, an opportunity presents itself to do some specialized research. Just after I finished my book in 1999, I came upon the chance to meet a descendant of the renowned 19th-century cast-iron maker J. W. Fiske. A friend gave me the number of Joseph Warren Fiske and I went to meet him at his home in Princeton, NJ. Joe Fiske was the great-grand-nephew of the founder, Joseph Winn Fiske, and had been running the business for years when it closed in 1986. He was very receptive to the idea of my doing an article about his family company.

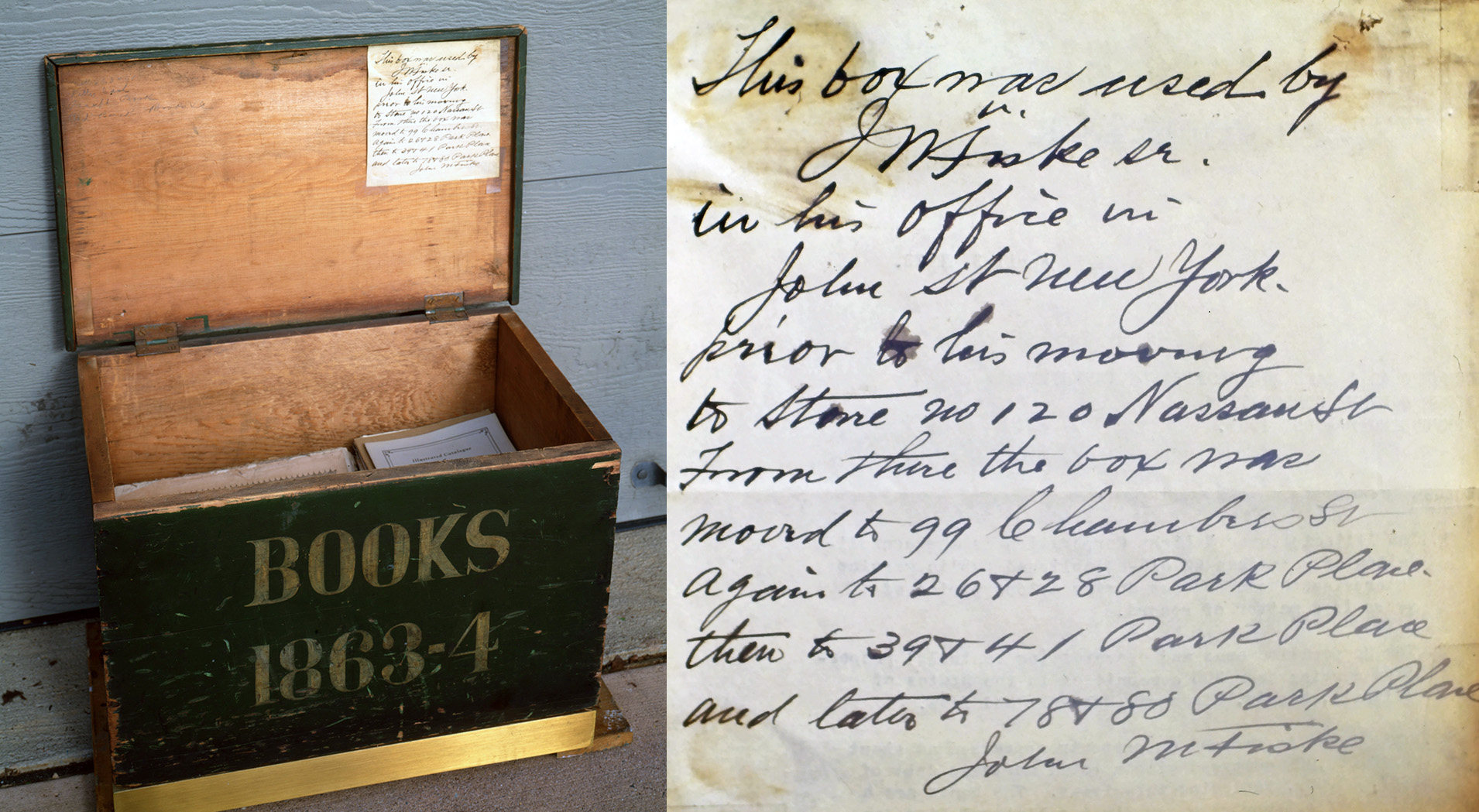

He said he had some old company papers in his garage that I could look through. After a quick inspection I realized that his collection merited much closer scrutiny. [Photos: Barbara Israel]

Since 1985, when I started my business and soon afterwards when I started doing shows, I had heard plenty of references to the Fiske Company and many claims about how “they had a foundry in upstate New York” and “one in New York City” and “another one in Boston”. And I had noticed that the prestige of J. W. Fiske’s name seemed to have encouraged potential misattributions of unmarked products to him. So, I was excited to try to either confirm or refute these stories.

I drove regularly to Princeton to Joe Fiske’s house where I ended up spending a good deal of time. I literally took my office copier with me and installed it in his garage. Joe and his wife, June, were very gracious hosting me over quite a few weeks. The following research and information are taken from that work and the resultant article I wrote for The Magazine Antiques, published in the March 2000 issue.

I drove regularly to Princeton to Joe Fiske’s house where I ended up spending a good deal of time. I literally took my office copier with me and installed it in his garage. Joe and his wife, June, were very gracious hosting me over quite a few weeks. The following research and information are taken from that work and the resultant article I wrote for The Magazine Antiques, published in the March 2000 issue.

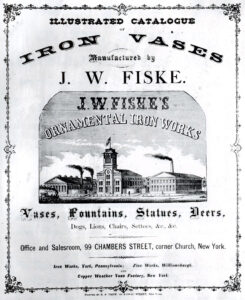

I already owned a number of facsimile Fiske catalogues and was familiar enough with his output to know that he had showcased a multitude of classical statues, urns, garden seats and fountains, prior to my deep dive into the company papers in Joe Fiske’s garage. [Photo: Cover of the J. W. Fiske Illustrated Catalogue, circa 1870s, reprinted in 2014.]

In 1858, J. W. Fiske established a company that would become a prominent fixture in the American decorative arts landscape of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. His enterprise quickly gained recognition for its diverse product range and innovative business practices. Initially based in Boston, Fiske’s ambition led him to expand to New York City by 1865, where he set up a showroom at 120 Nassau St. This strategic move placed him at the heart of America’s burgeoning commercial center, allowing him to tap into a wider market and establish crucial business relationships. Most of the contemporaneous evaluation statements about the Fiske Company were very positive but an entry in the 1872 R. G. Dun and Company Report–an agency that published assessments of businesses in the United States and Canada from the 1840s through the 1890s–stated that “the feeling in the trade is not altogether favorable to his mode of doing business, although his respectability is not questioned.”

One of his major competitors was J. L. Mott Iron Works of New York City and they locked horns a fair number of times over the years. Following is an example of one such incident. The rivalry between the Fiske company and J. L. Mott Iron Works is illustrated by their competition for providing and installing a large municipal fountain in Chambersburg PA. [Depicted above, photos: Jeni L. Sandberg] According to a file in the Kittochtinny Historical Society in Chambersburg, the two New York firms and another manufacturer, Robert Wood of Philadelphia, submitted designs for the fountain. When none of them were adopted, Fiske offered another design which was immediately accepted, but the price, a steep $3000,“ prevented purchase”. Early in 1878 Jordan L. Mott Jr. (1829-1905) proposed that the town buy the fountain he had displayed at the Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia in 1876. Just as this offer was about to be accepted the town reopened negotiations with Fiske, ever the persuasive salesman, who sent them a new design at the much-reduced price of $1700, delivered. He won the contract.

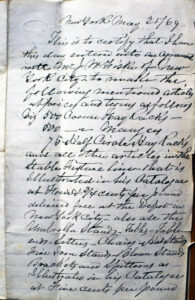

The biggest surprise I found among Mr. Fiske’s papers was the actual agreement that his ancestor had signed in 1869 with E. G. Smyser of York, PA, by which Smyser’s firm, Variety Iron Works, would supply Fiske with “all the Umbrella Stands-Tables-Table Ends-Settees-Chairs-Hat Stands, Fine Iron Stands-Flower Stands, Brackets and Spittoons…I [Smyser] also further agree not to make or cause to be made ‘directly or indirectly’ any casting or pattern furnished by J.W.F. for any other party, or purpose, without the consent of said Fiske.” This guarantee addressed the ever-present issue of the appropriation of designs that went on among the makers of metal ornaments. [Photo: Barbara Israel]

The biggest surprise I found among Mr. Fiske’s papers was the actual agreement that his ancestor had signed in 1869 with E. G. Smyser of York, PA, by which Smyser’s firm, Variety Iron Works, would supply Fiske with “all the Umbrella Stands-Tables-Table Ends-Settees-Chairs-Hat Stands, Fine Iron Stands-Flower Stands, Brackets and Spittoons…I [Smyser] also further agree not to make or cause to be made ‘directly or indirectly’ any casting or pattern furnished by J.W.F. for any other party, or purpose, without the consent of said Fiske.” This guarantee addressed the ever-present issue of the appropriation of designs that went on among the makers of metal ornaments. [Photo: Barbara Israel]

This collaboration set Fiske apart from his competitors and was a unique approach to manufacturing. Rather than having his own costly foundry, Fiske operated independently relying on other foundries for casting while maintaining strict control over design and finishing processes. This innovative business model allowed him to focus on creativity and quality control while minimizing massive overhead costs. Depicted at left is a cast zinc figure of the Venus de Milo made by Seelig and Company, marked J. W. Fiske, an example of a Fiske design and a Seelig production. Note that the designer adapted the antique model to include arms! And those arms are derived from yet another antique model, the Venus D’Arles. [Photo: Sharyn L. Peavey]

This collaboration set Fiske apart from his competitors and was a unique approach to manufacturing. Rather than having his own costly foundry, Fiske operated independently relying on other foundries for casting while maintaining strict control over design and finishing processes. This innovative business model allowed him to focus on creativity and quality control while minimizing massive overhead costs. Depicted at left is a cast zinc figure of the Venus de Milo made by Seelig and Company, marked J. W. Fiske, an example of a Fiske design and a Seelig production. Note that the designer adapted the antique model to include arms! And those arms are derived from yet another antique model, the Venus D’Arles. [Photo: Sharyn L. Peavey]

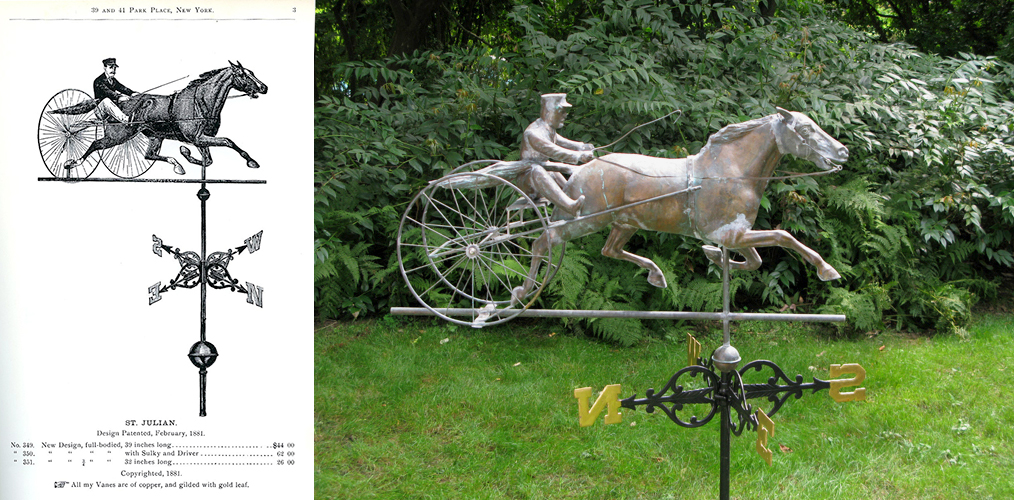

I had found the answer to the question of where Fiske had his foundry – he didn’t have one at all. Soon after that I found a copy of a contract from 1892 when Fiske joined with Moritz J. Seelig and Company of Williamsburg, Brooklyn, to make his zinc objects. Seelig was a German immigrant who produced and retailed zinc statues that the Fiske firm marked as its own. His copper weathervanes that he later became so renowned for were also made at the same factory. [Photos: J. W. Fiske Illustrated Catalogue, circa 1892 – 1907; J. W. Fiske St. Julian weathervane, Charles A. Johnson]

Fiske decided early on to mark many of his pieces with the company’s name, the showroom address and sometimes even the patent date. Thus, his products are easily identified and should not be confused with unmarked pieces. Again, I was satisfied that my answer to attributions was found in the reliability of Fiske’s markings. See above examples of his distinctive marks. [Marks photos: Barbara Israel Garden Antiques]

Because the company frequently changed names and addresses, these marks are useful in dating the objects. And, since designs and patterns were almost universally duplicated among many makers, it is almost impossible to differentiate the designs of one or another without a solid provenance or the presence of a mark. This practice of marking pieces also helped establish the Fiske name as the mark of quality in the ornamental iron and zinc industry thereby promoting his brand.

As fine a retailer as Fiske was, he was one of many producers of similar work. Although his firm was not the largest, he succeeded in being at the forefront of his industry, mostly through ingenious business practices, not the least of which was contracting out the casting of iron and zinc.

My time in Joe Fiske’s garage turned up a lot of information that was surprising and hugely helpful. I am grateful to him to this day for allowing me the privilege of unearthing the history of his family company.

Paul Manship’s Whimsical Bronze Gates

By Eva Schwartz

Years ago we put together an issue of Focal Points that highlighted some of the delightful statues and other decorative gems that are tucked away in Central Park. We don’t often return to a subject we’ve covered, but I felt compelled to revisit a particular pair of bronze gates by the esteemed American sculptor, Paul Howard Manship (1885-1966). I pass these little treasures often, as they’re just north of the Metropolitan Museum on Fifth Avenue between 84th and 85th Streets–just a few short blocks from our office. They mark the entrance to the Ancient Playground, an adventure playground designed by civic architect Richard Dattner in 1973 that takes inspiration from the Metropolitan’s Egyptian art collection, including its majestic Temple of Dendur (not to mention Cleopatra’s Needle, the circa 1425 BCE obelisk installed in Central Park in 1881). Thematically, the gates, which depict five of Aesop’s classic fables, don’t particularly relate to the forms of the playground, but there’s a reason for that: the gates have not always been at their current location. They had previously served, from 1953 to 1973, as the entrance gates for a different playground entirely–one that once existed a bit to the south of the present site. To make way for the new Met wing that would house the Temple of Dendur, the old playground was razed and the gates moved to the Ancient Playground. After suffering some devastating vandalism in the mid-1970s, they were put into storage for decades before undergoing restoration and reinstallation in 2009.

The old play space where the gates had first been installed had been a memorial playground named after William Church Osborn (1862-1951), the President of the Metropolitan Museum from 1941 to 1947. A prominent lawyer and philanthropist, Osborn served for 50 years as the president and chairman of the board of one of the city’s oldest and most reputable charities, the Children’s Aid Society. In 1952, Osborn’s friends and admirers raised money for a memorial to be placed in Central Park, and Robert Moses (1888-1981), the influential parks commissioner, suggested that Manship would be the right artist for the project. Manship had, after all, previously designed a monumental set of gates, called the Rainey Gates, for the Bronx Zoo in 1932 (installed 1934).

In fact, Manship paid homage to the older gates in his new design; atop the granite pillars flanking the Osborn gates are the very same Group of Bears and Group of Deer seen on the Rainey Gates. The animals are configured differently as they’re clustered together on the Osborn pillars, as opposed to the linear Rainey arrangement, but the same maquettes were used for both. A much larger version of the Group of Bears now guards the entrance to the Pat Hoffman Friedman Playground, at the southern edge of the Metropolitan Museum. [Photos: Rainey Gates, Carol M. Highsmith, Library of Congress (left); Group of Bears, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons]

Befitting a children’s park, the Osborn gates depict five of Aesop’s ancient fables: The Peacock and the Crane, The Wolf and the Lamb, The City Mouse and the Country Mouse, the Fox and the Crow, and the Hare and the Tortoise, each executed with the most captivating animals set off by elegant, almost graphically-rendered foliage. The animal protagonists (and antagonists) of Aesop’s tales are visited by four charming squirrels perched along the gates’ top rails, and three little frogs, poised to leap along one bottom rail. In amongst these animals and vegetal flourishes are five plaques inscribed with pithy nuggets of Aesop’s wisdom (such as, “Woe to the lamb that disputes the wolf”). I particularly love the dynamism achieved by the asymmetrical design of these gates. It brings to mind the same balance-through-asymmetry that is central to Japanese art. It’s notable that, although quite a late work in Manship’s oeuvre, the gates exhibit the consistently pared-down, stylized aesthetic that was evident from the artist’s earliest days. [All detail photos of Osborne Gates: Eva Schwartz]

Paul Manship, whose most famous work is the 1934 Prometheus fountain at Rockefeller Center, was inarguably one of the most prolific and well-regarded sculptors of the early to mid-twentieth century. He was born in St. Paul, MN, but moved early on to Philadelphia to study at the Philadelphia Academy of Fine Arts, and later to New York where he worked as a studio assistant for Solon Borglum (1868-1922) and Isidore Konti (1862-1938). Konti encouraged him to apply for a competitive fellowship at the American

Paul Manship, whose most famous work is the 1934 Prometheus fountain at Rockefeller Center, was inarguably one of the most prolific and well-regarded sculptors of the early to mid-twentieth century. He was born in St. Paul, MN, but moved early on to Philadelphia to study at the Philadelphia Academy of Fine Arts, and later to New York where he worked as a studio assistant for Solon Borglum (1868-1922) and Isidore Konti (1862-1938). Konti encouraged him to apply for a competitive fellowship at the American  Academy in Rome, which Manship secured in 1909. He studied there for three years, honing his skill and his appreciation for ancient classical sculpture. Upon his return to the United States in 1912, he quickly gained prominence. Often heralded for being a Modernist, Manship drew inspiration from the severely schematic forms of Assyrian and archaic Greek sculpture, in addition to the rhythmic linearity of Indian and Asian art, resulting in a distinctive style. [Seen here is an example of the type of archaic Greek sculpture that Manship would have looked to as a model—a lion from 570-550 BC, in the collection of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Manship’s early figural works, like Dancer and Gazelles (1916), the example above at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., also drew heavily on the forms of ancient Indian sculpture, with which he became familiar during his years in Europe.] Serendipitously, Manship’s “archaic” approach worked extremely well with the stylized architecture and interiors of Art Deco, making him one of the most successful sculptors of the period. His pieces had a modern look yet were still grounded in traditional figurative form–a feat that won him a broad swath of admirers at a time when abstract art was on the rise. [Photos: Prometheus Fountain LBM1948, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons; archaic Greek lion, Daderot, public domain, via Wikimedia Commons; Dancer and Gazelles, Mark Landon / Wikimedia Commons]

Academy in Rome, which Manship secured in 1909. He studied there for three years, honing his skill and his appreciation for ancient classical sculpture. Upon his return to the United States in 1912, he quickly gained prominence. Often heralded for being a Modernist, Manship drew inspiration from the severely schematic forms of Assyrian and archaic Greek sculpture, in addition to the rhythmic linearity of Indian and Asian art, resulting in a distinctive style. [Seen here is an example of the type of archaic Greek sculpture that Manship would have looked to as a model—a lion from 570-550 BC, in the collection of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Manship’s early figural works, like Dancer and Gazelles (1916), the example above at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., also drew heavily on the forms of ancient Indian sculpture, with which he became familiar during his years in Europe.] Serendipitously, Manship’s “archaic” approach worked extremely well with the stylized architecture and interiors of Art Deco, making him one of the most successful sculptors of the period. His pieces had a modern look yet were still grounded in traditional figurative form–a feat that won him a broad swath of admirers at a time when abstract art was on the rise. [Photos: Prometheus Fountain LBM1948, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons; archaic Greek lion, Daderot, public domain, via Wikimedia Commons; Dancer and Gazelles, Mark Landon / Wikimedia Commons]

When the William Church Osborn Memorial Gates were completed in early 1953, Manship showed them off to friends at his East 72nd Street studio before escorting the work to Italy to be cast by the Florentine foundryman, Bruno Bearzi (1894-1983). They were the last important piece to be completed at Manship’s Upper East Side studio as he moved downtown shortly thereafter. Late in his career, he received several more commissions at Robert Moses’ behest, including multiple works for civic buildings and another major production for Central Park: the Lehman Gates at the entrance to the Children’s Zoo.

Next time you’re strolling down Fifth Avenue, or through Central Park, take note of these enchanting works of art. My hunch is you’ll be happy you did.