Encounters with Animals in the Garden

By Barbara Israel

The very first time I bought a group of garden ornaments from an estate I became immersed in a search for a stone fox. The owner’s garden was illustrated in The American Woman’s Garden by Rosemary Verey and Ellen Samuels and I had poured over the pictures of it while waiting for the big pick-up day. When the day finally came it was utter confusion with too many statues and too few helpers. But, in the afternoon a light bulb went off in my head, “where is that fox that I saw in the pictures?” I was convinced it still had to be there. It wasn’t a large property but it was overgrown with shrubs, vines and rampant ground cover. I thrashed through the underbrush and at last found two little ears peeking out from the top of a hydrangea bush. I was charmed by his alert expression and fine thick tail as he emerged from his hiding place where he’d been surprising visitors for years. Animal statues provide amusement in the garden, especially if they’re life-like and give a start to the viewer. They liven up an otherwise static landscape and add an informal note to a natural garden.

Years later one of my clients bought a cast-iron stag from me and placed it in a field just beyond her garden. The day after Halloween she discovered it had been knocked over onto its side. It was pretty clear to her that some mischievous local kids had been up to no good on that special night of rowdiness. But when her husband inspected the stag closer he got a surprise. There were huge scratches all over it indicating that a live buck had been lured into combat by the energetic naturalism of the statue.

Some animal statues attain the sublime. I recently bought two figural groups of does with their fawns from the Doris Duke estate in Hillsborough, NJ. They were originally purchased in Europe by James Buchanan Duke (1856-1925) in the early 20th century for his beloved Duke Farms. Modeled by Pierre Rouillard (1820-1881), one of the finest though less-known French “animalier” sculptors, they were cast by the Val d’Osne foundry. Larger than life-size in scale, their stature and refined fluid forms imbue them with a striking immediacy. We had them placed among the apple trees in our orchardá and my husband and I have been fooled more than once into thinking that we had unwelcome four-legged visitors. In fact, they are two amazingly real statues. But beyond being merely naturalistic, these statues are extraordinary artistic achievements– sculpture at its finest. Occasionally I come across something that satisfies every category of perfection and these two deer groups are exactly that.

Pierre Louis Rouillard: Animalier Distingue!

By Katy Keiffer

This spring Barbara Israel viewed the ornaments for sale at the Doris Duke estate in Hillsborough,NJ. As she describes above she was stunned by the two groups of does and fawns (Biches et Faons). The finesse of the modeling, the effortless realism and the impressive scale of the statues convinced her rapidly that these were the best of the best.

Modeled by the master “animalier” Pierre Louis Rouillard (1820-1881), the two groups of doe with fawn demonstrate the virtuosity of this mostly forgotten nineteenth-century French sculptor. Cast by Rouillard’s longtime collaborators at the prestigious Val d’Osne Foundry in Haut-Sur-Marne, these pieces are rare acquisitions.

Rouillard won his first major commission when he was 20–a dramatic sculpture of a dog battling a cat designed for the Duc d’Orleans. Rouillard’s close study of anatomy in the Museum of Natural History in Paris, while attending the Ecole des Beaux Arts, paid off in his ability to render animals with extraordinary verisimilitude.

Throughout Rouillard’s career he strove to achieve absolute truth in the expression and anatomy of his animal subjects. For most sculptors in this genre animals were imbued with human emotion, but Rouillard did not subscribe to anthropomorphism. His beasts are completely real. Though he occasionally executed commissions of people, his work remained firmly rooted in the animal kingdom.

Rouillard’s willingness to work on a large scale brought him to the attention of the great architects of his day and helped him to secure major municipal commissions throughout France, including designing for the Trocadero and the Fountain at Place Saint-Michel. The breathtaking sculpture of a horse with a farrow, currently residing in front to the Musee D’Orsay in Paris, was originally one of the Trocadero sculptures created for the 1878 World’s Fair. Rouillard also executed commissions in other countries with, perhaps, his greatest project being a commission from the Sultan of Constantinople for a suite of 24 groups of animals, massive ornamental vases and a frieze for the palace.

Unlike many of his contemporaries, such as Antoine-Louis Barye, Henri Alfred Marie Jacquemart, Francois Pompon (a student of Rouillard) and Emmanuel Fremiet, Rouillard did not capitalize on the vogue for tabletop animal bronzes so popular in France in the second half of the nineteenth century. Though Rouillard produced a number of these pieces for the Christofle Company, a well-known jeweler and dealer of objets vertus of the time, he much preferred working on a monumental scale and it is for these majestic sculptures that he is so justly admired.

Sadly, many of Rouillard’s models were destroyed during the brief period of the Paris Commune. In 1968 the Ecole des Arts Decoratifs, where he taught for 41 years, destroyed most of the remaining models he had left as a bequest to the school. The failure to preserve Rouillard’s original models and his lack of an heir to oversee his legacy have been major factors contributing to his relative obscurity today.

Reveries from Running Duck Farm

By Nan Zander

It’s been roughly eight years since our daughter decided she needed to raise chickens. It started small with a nice group of egg layers. She incubates the eggs of carefully chosen breeding pairs, shows the hand raised birds at county fairs, sells birds, advises new flock owners and is trying to revive an extremely rare heritage breed. This naturally led to raising birds for meat, and now the flock is almost a full-time job and a huge part of our lives. It would have been easy for me to give up on gardening when our feathered friends first started taking over Running Duck Farm. Chickens and ducks are messy, stubborn, voracious and loud, but they have an equal number of qualities to recommend them.

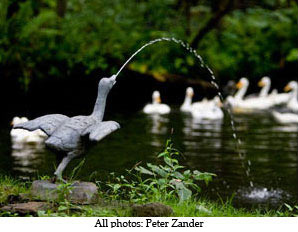

On this hot, late afternoon all the ducks are lounging on the grass in the shade of our big Rivers Beech. The English Calls and Indian Runners lie with their bills tucked under their wings enjoying group naptime. In a while one will decide naptime is over, wake up the others and they’ll march single file into the pond–babies at the rear, wagging their little tails and quacking happily. Before we had ducks, I spent years cultivating a natural-looking water garden, with Pickerel Rush, various iris, grasses, Petasites, Primulas and one beautiful lotus a friend gave me to nurse back to health. “If anyone can grow this, you can,” she said. Three years later, the most perfect lotus blossom I’ve ever seen greeted me one summer morning. The exquisite, pale yellow flower floated on crystal clear water, with schools of naturalized goldfish admiring it from below. I was ecstatic. Around that time the first ducks joined our flock. The lotus was never seen again. The fish went next, then the Yellow Flag! Ducks love sifting through the mud for bugs and bits of vegetation so the clear water was history as well. Not long ago I added a lead fountain of a running duck to spout water into my pond. It keeps the water clear, is a wonderful replacement for my long-lost flowers and adds the pleasant sound of splashing water to what is once more an idyllic scene. The best part is watching the ducks line up to take turns under its shower.

Ducks love to eat bugs both in and out of the water, but chickens are a big help with this as well. An old stone trough under one of our spigots used to collect water all summer long. Mosquito larvae need standing water and thrive in decorative water features like troughs and birdbaths. This year I moved the trough to the front of the chicken coop next to an unusual pink Viburnum, in place of our usual plastic chicken waterers. It is much prettier and the hens are adorable as they perch on the trough’s edge to drink. Not only do they jockey for position on the trough, but they practically fight over the immature mosquitos swimming below. Now when friends complain about the awful bugs that plague them all summer I just smile knowingly.

Where the trough and Viburnum now reside there used to be a vibrant bed of tall wildflowers. The spot gets full sun all day and is quite frequently dry and dusty, which the flowers must have loved. Chickens bathe in dust, not water, and love nothing better than to dig a shallow hole in a nice flowerbed and hunker down in the sun. Then they flap around like fish out of water, making sure every feather is nicely dusted. Needless to say, after a short fight, I gave up on the flowers. They were replaced with four small, practically indestructible, globe boxwoods. Now the chickens dust-bathe to their hearts’ content and everyone is happy.

I will not, however, give up my nasturtiums. They grow up bamboo teepees near my herb garden, bloom like crazy and are easily picked for salads. Since they are next to the house, they are safe from marauding hens. Except Pigwidgeon. Pig was the first chicken we ever bought; she isn’t necessarily at the top of the pecking order, but she believes her status gives her carte blanche with my favorite flowers. When she thinks I am looking the other way, she will quietly sneak away from the flock and slowly but surely make her way over to the nasturtiums. She is drawn to the Whirlybird mix, Empress of India, Strawberries and Cream and whatever other beauties are twining up the poles. Maybe it’s the beautiful colors or the peppery taste she loves. Perhaps she is rebellious or does it for attention. I gently chase her away, hoping she will still be around to play the game next year.

As a gardener, I’m especially grateful for what the “girls” leave behind. Chicken manure is the richest of all animal manures in nitrogen, potassium and potash. In our case, it’s combined with bedding made of wood shavings. The mixture composts for one season and is ready for use the following spring. I spread it over my beds, plant directly into it, never worrying about free-ranging birds pecking about in beds fertilized with their own compost. We no longer use any chemicals on the property and, while we have a wicked crop of weeds in much of the lawn, the flower gardens are beautiful. My huge bed of pachysandra is beautiful too. Every spring I rake out the areas most matted with dead leaves, always taking special care with the front edge that shows the most. Early this spring I came home from work to a delightful surprise. Some kind soul had raked out the front edge of the entire curving bed and made a neat pile of the leaves, about six inches away. How nice! It took only seconds to locate the gardeners. A group of baby Cornish Crosses were madly raking the next bed of pachysandra as they foraged for good things to eat. I was charmed, grateful for their unexpected assistance and struck by how much I enjoyed them. We had progressed from half-hearted tolerance to true, harmonious interdependence. The animals belong in the gardens, and the gardens wouldn’t be the same without them.

Animals at Belmont Mansion Nashville, Tennessee

By Katy Keiffer

In the antebellum South, Adelicia Acklen and her husband Joseph Acklen were that rare couple who shared similar tastes and aesthetic ambitions. The results of their union, not to mention their taste, is a sumptuous residence in Nashville, now home to Belmont University. While the house remains a gem of the pre-Civil War era, with its elaborate ironwork around the windows and marvelous cast-iron gazebos, it is the gardens and their ornament that interest us.

The spacious 180-acre property includes marble statuary, a zoo, a carriage house, fountains and stables. In addition, the Acklens had greenhouses, an art gallery and a bowling alley. Adelicia had traveled extensively in Europe, where she purchased statues for her gardens from the well-known American sculptors Randolph Rogers, William Rinehart, Chauncey B. Ives and Joseph Mozier who had established their studios abroad. However, like many Americans of the time, she was also enthusiastic about the cast-iron animal sculptures sold by such prominent firms such as Wood and Perot.

Wood and Perot was an important supplier of cast-iron ornament during the 19th century. Based in Philadelphia, and with an ancillary manufacturer in New Orleans, their catalogue of designs eventually exceeded 3,000 pieces. The firm was started in 1840 by Robert Wood, became Wood and Perot in 1858 and then Robert Wood and Co from 1868 until it folded in 1879. The Acklens would have been regular visitors to both locations between managing their extensive plantations in Louisiana and their regular shopping trips to Philadelphia and New York.

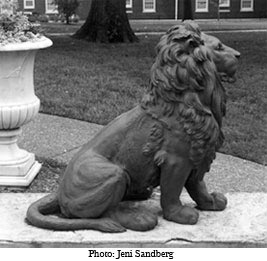

In addition to extensive furniture and architectural elements in the Wood and Perot catalogue, there were numerous animals, and it was these, according to Mark Brown, Executive Director of Belmont Mansion, that enchanted Adelicia. Belmont Mansion boasts pairs of deer, lions, pairs of dogs and a very rare casting of a Newfoundland.

The “Newfoundland”, in particular, was made popular by Hayward Bartlett and Company, a foundry based in Baltimore. They used the term to describe a variety of dogs including the Chesapeake Bay retriever, the Curly Coated Retriever and the Irish Water Spaniel, breeds that were often crossed with the original Newfoundland breed. While Hayward Bartlett and Co were the original designers of the Newfoundland, theirs is now often referred to as the “short body” of 44 inches. Wood and Perot used and produced the same model as well as casting a 64-inch version.

Popularized by the British, animal sculptures began making their way into American gardens around 1860. J.W. Fiske was another prominent cast-iron ornament foundry that offered a variety of dogs and other animals in their catalogue. Wood and Perot and J.W. Fiske competed with each other and with Hayward, Bartlett and Company. All three firms frequently copied each other’s designs for their own customer base. Because of the popularity of animal subject matter there were dozens of foundries that manufactured cast-iron animals.

In contrast to the American taste for the benign character of animal sculpture, the French and British favored considerably fiercer, more combative examples. The Belmont lions are a perfect exponent of the American approach to nature–tamed, reposeful and unthreatening. The Belmont seated lions are illustrated in the 1875 Robert Wood Co. catalogue and very few examples of this design are extant.

Cast-iron animal sculpture retained its popularity in America until around 1900. No doubt the rather peevish rebuke of the art critic Samuel Swift contributed to the demise of this charming fad when he described them as, “…the lurking dogs, the frightened deer and other fauna imperishably preserved in this merciless substance, whose coats were freshened once a year with new paint.” (House & Garden, 1903) As recounted in Barbara’s book, Antique Garden Ornament: Two Centuries of American Taste, Swift argued for the summary dismissal of all such ornament from American gardens. Fortunately for us, many examples have endured, and we can continue to enjoy the peculiar pleasure of seeing a cast-iron dog, stag, lion or hare on the steps or in the shrubbery of many American gardens, including the ones at Belmont Mansion.

____________________________

Animal statuary can be used in gardens of any design or size. Pairs can be placed on either side of a pathway in a formal garden and single statues can be tucked into flower beds to add charm to an informal design. One of my favorites is to perch a small bird statue on the edge of a birdbath or to stand a pair of bronze cranes in tall grass near a natural pond. Animal statues can run the gamut from regal to humorous. One of our family portrait specialties is posing our dogs with their immobile counterparts–that’s Zack between the cast-iron greyhounds and Piper with a pair of Coade stone greyhounds.