An Experienced Collector’s Eye

By Barbara Israel

I’m often invited to private houses to view garden ornaments people want to sell. Once in a while I come across someone with an exceptional eye. Pamela Humbert was one. In 2003 she invited me to her house in Bronxville, NY because she wanted to sell some statues. She explained that her family had owned the Pompeian Studios, an early 20th-century maker of fine garden ornament based in New York City. And, she proved to me very quickly she knew the field well.

Photos: Ben Cohen

On that visit Mrs. Humbert showed me a statue called Eve Repentant, a 19th-century life-sized marble of extraordinary quality. It was signed “E. S. BARTHOLOMEW ROME 1855”. I remember her saying “this is a really good one and it is the original.” It was exceptionally well carved depicting a seated Eve, her wavy locks cascading down her back, the apple and infamous serpent at her feet. I bought it from her and I can tell you that I paid well for that “good one”. She gave me a few tidbits about the statue–its provenance and the sculptor Edward Sheffield Bartholomew’s brief life span, 1822-1858. Knowing that it would go to the Winter Antiques Show we did a great deal of research on the Eve. Having found that the Wadsworth Athenaeum in Hartford had the exact same sculpture we contacted them to exchange notes. They explained that theirs was the original and ours was the copy. Following clue after clue we finally, at the last minute before the show, tracked down the complete origins of our statue and surprise, surprise, Pamela was right, ours was the original and the Athenaeum’s was the copy. This was confirmed by the Chief Curator of the Wadsworth, Betsy Kornhauser. We uncovered references stating that the Wadsworth’s Eve had been commissioned by Hartford citizens shortly after Bartholomew’s death in 1858 and the Wadsworth had for years been mislabeling their statue “1855”.

Last year I got a call from someone representing the estate of Mrs. Humbert’s. I was sorry to hear that she’d passed away but was definitely interested to see her personal collection. I met her designated representative in Bronxville where I was overwhelmed by an incredible amount of wrought iron: chaises, sofas, chairs, tables…masses of useful pieces of furniture but ones that weren’t necessarily for us. She also had a Buddha, a nice cast metal fountain figure of a heron, an average pair of stoneware urns and a number of small gravestones for her pet cats. There were two bronze statues that I assumed had been cast by Pompeian Studios, both very attractive and salable. I took photos of everything planning to make an offer on the few pieces that I was interested in. It all seemed pretty straightforward and nice but not a collection that was hiding another Eve Repentant. As I went to get in my car I noticed a small stoneware statue that was off to the side near the parking space. It was two jaguars on a base and it totally caught my eye. So, I snapped a picture of it and said to myself, “Wow, she really knew her cats!”

We ended up buying the jaguars and a number of other statues. Upon inspecting them in our workshop we found the base bore an incised signature with an animal head in a circle. We confirmed the signature read “E. Kemeys” and the animal head was a wolf’s. After a small amount of research we learned that the mark and his name were common knowledge in American fine art circles. No one was more surprised than I to discover that the jaguar statue had significant importance. Edward Kemeys was only the most important 19th-century American sculptor of animals! Pamela Humbert did it again–what a brilliant collector’s eye she had and I’m grateful to have been part of such an exciting find!

We ended up buying the jaguars and a number of other statues. Upon inspecting them in our workshop we found the base bore an incised signature with an animal head in a circle. We confirmed the signature read “E. Kemeys” and the animal head was a wolf’s. After a small amount of research we learned that the mark and his name were common knowledge in American fine art circles. No one was more surprised than I to discover that the jaguar statue had significant importance. Edward Kemeys was only the most important 19th-century American sculptor of animals! Pamela Humbert did it again–what a brilliant collector’s eye she had and I’m grateful to have been part of such an exciting find!

Still Hunt

Photo: Eva Schwartz

Edward Kemeys

By Katy Keiffer

Edward Kemeys (1843-1907) dominated the American animal sculpture field in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. His success lay in his remarkable ability to convey the power, majesty and personality of the wild animals he studied.

Born in Savannah, and working mainly in New York and Chicago, Kemeys was self-taught. Following his service in the Union Army in the Civil War and a failed stint as a farmer in Illinois, he moved to New York. Several biographical sketches mention Kemeys’ initial inspiration occurred while working on the construction of Central Park when he observed a sculptor at the Central Park Zoo modeling a wolf’s head. This prompted him to began his own study and sculpting of the Zoo’s animals, quickly developing his substantial skills. Perhaps this explains the inclusion of a wolf’s head inscribed in a circle in Kemeys’ signature.

By 1871, at the age of 28, he was ready to exhibit his plasters and bronzes at the American Institute of Art in New York City. Following the conclusion of the exhibition, Kemeys was awarded his first major commission; Hudson Bay Wolves Quarreling over the Carcass of a Deer was installed in Philadelphia at what is now the Zoological Gardens in 1872.

Thanks to boyhood summers spent on the Illinois plains, Kemeys’ true passion was for observing animals in their natural habitat. The money he earned from his Philadelphia commission enabled him to take the first of many trips out West where he observed animals caring for offspring, defending territory and engaged in hunting and eating. Over the course of his career, Kemeys spent months living in the wild, sketching live and dead animals and observing their relationships and characteristic behaviors.

Kemeys exhibited three sculptures at the Philadelphia Centennial Exhibition in 1876. In 1877, Kemeys traveled to both London and Paris where he exhibited work to critical acclaim and engaged in some formal training. He exhibited Bison and Wolves at the Paris Salon of 1878. His immediate competitors were the French animalier sculptors Antoine Louis Barye and Pierre Louis Rouillard (profiled in the Animals issue of Focal Points). He returned to the United States, disappointed by the French artists’ methods which relied on observation of animals in captivity. While the European animalier sculptors were popular in America, the relaxed and free modeling of Kemeys’ work combined with the psychological acumen of his portrayals made him a favorite here.

Kemeys’ work was popular with Theodore Roosevelt, whom he met in the 1880s while they were both contributing articles to the magazine, Outing, and whose patronage he enjoyed until his death in 1907. Kemeys’ efforts to document the dominant species of North American wildlife before the encroachment of the Westward expansion was a primary incentive for his prodigious output.

Prayer for Rain

Photo: Agriculture/Wikimedia Commons

In 1883 Kemeys’ professional career came full circle when Still Hunt, his life-size bronze of a panther was installed in Central Park. (In the below Central Park article we take you on a walking tour of the Park that includes the location of this bronze.)

He won numerous major commissions around the country. Kemeys is perhaps best known for the two standing bronze lions flanking the Michigan Avenue entrance to The Art Institute of Chicago. The lions were commissioned by Mrs. Henry Field as a gift for the 1893 opening of the Art Institute in its current location, and were installed in May 1884. His last major commission was the statue Prayer for Rain for the Johnson Fountain in West Side Park, Champaign, IL, dedicated on June 1, 1899. It depicts a Native American standing with arm outstretched and flanked by a seated panther and a stag; it is one of the rare Kemeys sculptures to feature a human.

Kemeys moved to Washington, DC in 1902 where he lived until his death in 1907. Kemeys’ widow Laura, also a sculptor, arranged a major retrospective at the Corcoran Gallery of Art, and subsequently donated most of his sculptures and plasters to the National Museum of American Art.

Reveries from Running Duck Farm

By Nan Zander

The Woodland Slope in Central Park’s Conservatory Garden is breathtaking this time of year. The Woodland Slope is a slightly secluded, gentle hillside enclosing the English (South) Garden, one of three distinct garden sections in the Conservatory Garden, the others being the Italian (Central) and the French (North). The Slope is a subdued counterpoint to the dramatic grandeur of the Italian Garden and should be a must on any visitors’ map of the Park. To me, a woodland garden is charming for its subtlety and lack of pretense. The random aspect of a certain fern growing alongside a rock, or a path meandering through the woods, or the reflection of a flowering tree in a stream can be as beautiful as a vivid June border in all its glory. I usually find any natural combination of woodland wildflowers perfect as is, so when care is taken in their planning and planting the result, as in the case of the Woodland Slope, is extraordinary.

All photos: Nan Zander

I visited the Woodland Slope in mid-April and was treated to a private tour by the head gardener of the Conservatory Garden, Diane Schaub. The garden was way ahead of its usual schedule after a week-long heat wave, so I saw many flowers that normally would not have been out yet. The Slope is a mix of native and non-native plants that have multiplied into a glorious mass of color and texture. Hellebores were at their peak during my visit; they were scattered all over the hillside and colored from whites, creams, chartreuse, to pink and deep maroon. The color harmonies Hellebores produce are to me one of nature’s most beautiful mysteries; you never know exactly what color you will have from one year to the next but they are always perfect. Various members of the Amaryllidaceae family were in full bloom all over the slope. There were Summer Snowflakes Leucojum aestivum as well as vast naturalized patches of Narcissus. These included “Pipit”, “Bravoure”, “Actaea” and “Geranium”, whose yellow and white heads stuck up here and there among naturalized sweeps of Mertensia virginica, the Virginia bluebells. The “Bishop’s Hat”-like soft yellow flowers of Epimedium x versicolor were also at their peak, set off above their mat of dark green foliage that is just tinged with bronze at this time of year. Purple Brunnera macrophylla added one last note of blue to the understory. It was a cold, damp day, so the foliage and flowers glistened softly and the hillside could not have been more magical.

The atmosphere in the Woodland Slope garden is intimate and poetic, and its size makes it easy to enjoy on a limited schedule. It is also quite secluded, almost like a path in your own woods, if your woods were perfectly planted and maintained by four gardeners and a crew of volunteers. Trees and shrubs serve to define it, and hide it from view on all sides, but are also a great part of the show. Viburnums, Fothergillas, Clethras, Deciduous Rhododendrons, Lilacs and Delaware White azaleas are among the flowering trees and shrubs that surround the Woodland Slope. On the day I visited the Lilacs were already blooming, a full month ahead of schedule. The Korean Spice Viburnum carlessiii was in full flower; its heavenly scent and perfect pale flower clusters make it one of my all-time favorites. Nearby the Viburnum was one of Diane Schaub’s favorites–a fairly young Aesculus parviflora. Commonly known as the Bottlebrush Buckeye, it puts on a spectacular show in July when it is covered with large, showy white flowers pointing skyward. In fall the white flowers are replaced by pear-shaped brown fruits and the foliage turns yellow. It is a stunning shrub, native to the southeast but hardy as far north as USDA zone 4.

The Woodland Slope is a lesser known aspect of the Conservatory Garden, but it is well worth a visit. Its intimate beauty is both refreshing and soothing, and it is full of the fortuitous plant partnerings that make a natural woodland so charming. Squeeze it into a busy day and I guarantee you will emerge re-energized. The Conservatory Garden can be entered through the Vanderbilt Gate, located at Fifth Avenue and 105th Street. It is open every day from 8am until dusk. You can also take a free tour from April through October, starting at the Vanderbilt Gate at 11am on Saturday mornings.

Osborn Gates

Sculpture Walk in Central Park

By Katy Keiffer

Photographs by Eva Schwartz

Central Park houses some of the most beautiful and under-appreciated examples of sculpture and outdoor ornament in the City. In response to this fact, we have devised a tour to bring some of our favorite objects to the attention of our readers. The tour takes roughly 40 minutes to walk and is well worth the effort, especially at this time of year!

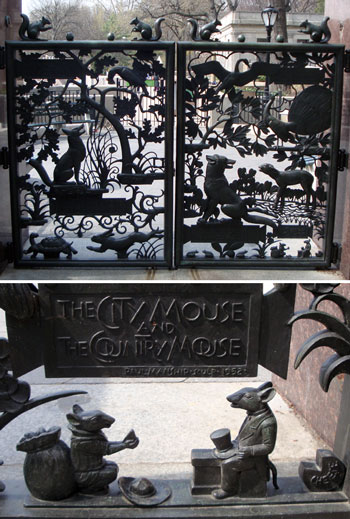

Start the tour at 85th and Fifth Avenue at the entrance to the Ancient Playground, so called because of its proximity to the Egyptian Wing of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. There are a fine pair of bronze gates designed by American artist Paul Manship (1885-1966). Manship was a major innovator in the field of modern sculpture and a forerunner of the Art Deco style and is perhaps most famous for the monumental Prometheus (1933) at Rockefeller Center. The Osborn Gates, named for William Church Osborn a former president of the Met, illustrate a selection of Aesop’s fables and are aesthetically reminiscent of ancient Assyrian, Indian and Asian works of art–of which Manship was an avid student. Several months ago Barbara discovered the gates, after having lived in the neighborhood for decades she was incredulous that she missed them. It turns out that the gates were only reinstalled in September 2009 after having been in storage since the early 1970s!

Continuing the tour, stroll down Fifth Avenue, entering the Park on the SW corner of 79th Street. Choose the path to the left and continue to bear left at the fork, proceeding into the fenced-in James Michael Levin playground. Inside the playground is the superb Sophie Irene Loeb Fountain portraying figures from Alice in Wonderland. The fountain honors the life and work of journalist and social worker Sophie Irene Loeb, founder of the Child Welfare Board of New York City. Sculpted by Frederick George Richard Roth (1872-1944) and installed in 1935, the fountain provides a whimsical focal point in an otherwise arid play space. From 1934-1936, Roth was the head sculptor for the New York City Department of Parks and Recreation under the WPA. Examples of his work can be seen throughout the Park, and particularly at the Zoo. Other examples of his work are highlighted below.

Sophie Irene Loeb Fountain

Leaving the playground, take the middle fork to the bridge ahead. Walk north under the bridge and make a hard left at the light post. Follow the rise up to the right and continue on to the East Drive. Turn right at the drive and walk north half a block. On the left side of the drive, look up at the rock outcropping to view Still Hunt, a life-sized bronze of a crouching panther, by Edward Kemeys, the American sculptor profiled above. The placement of this piece is so perfect, so naturalistic–it feels as if the big cat could spring at any moment!

Continuing south on the East Drive to the boathouse on the right, turn into the path leading along the pond edge. At the south end of the water, note the charming little passage, overhung with forsythia to your left. On the Bethesda Terrace, you’ll see two beautiful tall poles with elaborate finials on either side of the entrance to the pond. Crossing the terrace southward, take time to admire the remarkable carvings on either side of the staircases leading up to street level. The balustrade features exquisite roundels of birds, animals and flora (detailed below), designed by Jacob Wrey Mould (1825-1886). Mould was a British designer, architect and linguist who collaborated extensively with Olmsted and Vaux, Central Park’s principal architects. He was greatly taken with Moorish design and this sensibility is evident here. Belevedere Castle in Central Park is also attributed to Mould, along with a number of the Park’s bridges and passageways. For other locations in New York City, check out the Mould-designed promenade at Morningside Park and the fountain at City Hall Park.

At the top of the stairs, choose the right hand side of the Mall. With the bandshell on your left, take a right and stroll over to the bust of Beethoven then continue on a right hand diagonal to the magnificent Eagles and Prey by Christophe Fratin (1801-1864). Fratin was a highly successful French sculptor of animals whose work is represented in the Louvre and the Wallace Collection, London, among others. Installed in 1863, this bronze is the earliest work of art to be placed in any New York City park. It was a gift from Gordon Webster Burnham, a prominent industrialist of the day.

Walking south on the Drive, view the Sheep Meadow on your right, and the Literary Walk on your left. Just about a block from the Eagles is the Indian Hunter, by John Quincy Adams Ward (1830-1910). Installed in 1869, this was the first sculpture by an American artist to find a home in the Park. Ward was primarily known for his portrait busts, seen in many locations in New York City. There are three other examples of Ward’s work in Central Park–The Pilgrim, 7th Regiment Memorial and William Shakespeare.

Eagles and Prey, Indian Hunter and Balto

Heading south and east, cross the Drive, then turn north briefly to find the stairs down to a lower level. As you do, look northward to see the Frederick G. R. Roth sculpture of Balto, the illustrious sled dog. This celebrated canine led a team to snowbound Nome, Alaska, delivering serum to combat the diptheria epidemic that was ravaging the city in 1925. The statue was dedicated later that same year, with Balto himself traveling from Alaska for the unveiling.

Lehman Gates

Turning south again, pass under the bridge which brings you to the Children’s Zoo entrance on the left. The entrance is marked by the Lehman Gates, designed by Paul Manship and erected in 1961. The gates are comprised of granite pillars surmounted by a central bronze figural group of a boy gamboling with goats and seated boys playing panpipes at each end, the whole joined by a scrolling vine on which are perched small birds.

Honey Bear

Just past the gates on the left is a very charming frog weathervane worth noticing. Straight ahead is a brickwork arcade topped by the legendary Delacorte Musical Clock complete with dancing animal musicians that circle the clock every half hour. In a niche to the right is a full-size bronze figure of bear standing upright and in animated pose. The sculpture, Honey Bear, also by Frederick G. R. Roth and dating to circa 1935, functions as a fountain with water spouting from five frogs around the base. Its companion niche figure, Dancing Goat, has five small ducks at its base.

To complete the tour, turn left just past the arcade, and as you exit this area be sure to look at a final example of head sculptor Frederick G. R. Roth’s work, a bas-relief from the original monkey house at the top of the building.

_______________

We look forward to our next newsletter that will feature the extraordinary and far-reaching influence of Greek and Roman classical statuary on the garden ornament styles of later centuries.