Treasures of the Hudson River Valley

By Barbara Israel

The Hudson Valley is filled with extraordinary houses and gardens that were built along the scenic backdrop of the river. Miraculously, many of them have been preserved and provide us with examples of how people lived in past centuries. Initially the Hudson River and its Valley offered its earliest inhabitants opportunities for trading, farming and fishing. When European settlers arrived in the 17th century they were quick to take advantage of what a river of this magnitude could provide in the way of trade and commerce. As the settlers prospered they bought up great tracts of land, and the stage was set for the development of grand properties along the banks of the Hudson.

The Hudson Valley is filled with extraordinary houses and gardens that were built along the scenic backdrop of the river. Miraculously, many of them have been preserved and provide us with examples of how people lived in past centuries. Initially the Hudson River and its Valley offered its earliest inhabitants opportunities for trading, farming and fishing. When European settlers arrived in the 17th century they were quick to take advantage of what a river of this magnitude could provide in the way of trade and commerce. As the settlers prospered they bought up great tracts of land, and the stage was set for the development of grand properties along the banks of the Hudson.

Growing up in New Jersey I was always entranced by the views up and down the Hudson as we crossed the George Washington Bridge. I never thought anything about the river’s historic use until I took a road trip with my dad to visit one of his relatives in New Baltimore, NY, south of Albany. Polly Sherman was well into her 80s and had lived in the same house that had been in her family for years. It was a total time warp, dark and dreary, paint peeling, untouched for many years, but literally overhanging the river with a dock that abutted the house. I found here fascinating and she told me that she was a genealogist. One of her discoveries was that we were related to the Bronck family for whose farm the Bronx was named. She explained that her ancestor, Joseph Sherman, had had a lively trade in mahogany from his riverfront house. Then she showed us an 18th-century mahogany grandfather clock that she had inherited from him. It had always been in the house and had been passed down in the family. She wanted to give it to my dad as the nearest Sherman relative. His name was Joseph Sherman Frelinghuysen. When my parents’ estate was divided in 2006 I ended up with the wonderful Sherman clock and treasure it as a tangible piece of Hudson Valley history.

My focus on the Hudson River Valley and its inestimable natural gifts has changed in recent years. It is the historic use of the landscape by its many inhabitants that is totally compelling to me now. The 19th-century Hudson Valley produced the first American landscape specialist, Andrew Jackson Downing (1815-1852) who was born in Newburgh, NY. In the few years between his first noteworthy book in 1841 and his death 1852 he managed to influence landscape tastes and practices in the entire country throughout the 19th century and well into the next Until Downing no one had even imagined that there would be architects specially trained to design the landscape. (Photo: View of the Hudson from Kykuit, Pocantico, NY/Barbara Israel)

My focus on the Hudson River Valley and its inestimable natural gifts has changed in recent years. It is the historic use of the landscape by its many inhabitants that is totally compelling to me now. The 19th-century Hudson Valley produced the first American landscape specialist, Andrew Jackson Downing (1815-1852) who was born in Newburgh, NY. In the few years between his first noteworthy book in 1841 and his death 1852 he managed to influence landscape tastes and practices in the entire country throughout the 19th century and well into the next Until Downing no one had even imagined that there would be architects specially trained to design the landscape. (Photo: View of the Hudson from Kykuit, Pocantico, NY/Barbara Israel)

In 1851 Downing went searching for a business partner in England and came across Calvert Vaux, a Gothic Revival trained architect whose watercolors showed a particular appreciation of the art of the outdoors. He hired him to return to America and soon enough Vaux became a partner in Downing’s firm. When Downing died the next year Vaux took over the firm and continued for many years as a proponent of the picturesque landscape garden. Vaux’ later collaboration with Frederick Law Olmsted on Central Park, certainly his most important commission, converted many of Downing’s ideas into reality.

In the 1830s and 40s just as Hudson Valley houses were updated to prevailing 19th-century styles so were their gardens designed or reworked to reflect the latest fashion. The existing trend was the picturesque style that Downing and Vaux revered. It was characterized by curving pathways, sinuous roads, asymmetrical layouts, seats focused on a view, and the use of rustic elements and natural features. Sunnyside, Washington Irving’s house in Tarrytown, was created as a picturesque house and the garden followed suit. Designed around 1835 by Irving himself, and his friend George Harvey, it epitomized a Downing garden. (Photo: Sunnyside/Barbara Israel).

In the 1830s and 40s just as Hudson Valley houses were updated to prevailing 19th-century styles so were their gardens designed or reworked to reflect the latest fashion. The existing trend was the picturesque style that Downing and Vaux revered. It was characterized by curving pathways, sinuous roads, asymmetrical layouts, seats focused on a view, and the use of rustic elements and natural features. Sunnyside, Washington Irving’s house in Tarrytown, was created as a picturesque house and the garden followed suit. Designed around 1835 by Irving himself, and his friend George Harvey, it epitomized a Downing garden. (Photo: Sunnyside/Barbara Israel).

Around 1840, the recognized architect and author of Rural Residences, Alexander Jackson Davis (1803-1892) was hired to redesign Montgomery Place, a large property further north on the Hudson. After work was finished on the house the owners Cora Livingston Barton and her mother Louise Livingston consulted Downing on the grounds. The lively correspondence concerning their purchases of trees and shrubs from him reveals an exceedingly polite friendship between the parties.

In an 1848 letter to Cora L. Barton, Downing wrote, “I suppose Montgomery Place is looking very perfect this fine leafy season. I have also been making some little improvements in my own garden–and especially building a rustic summery house which we call the “hermitage”, and which I think is so much in your own taste that I should be heartily glad to show it to you.”

In an 1848 letter to Cora L. Barton, Downing wrote, “I suppose Montgomery Place is looking very perfect this fine leafy season. I have also been making some little improvements in my own garden–and especially building a rustic summery house which we call the “hermitage”, and which I think is so much in your own taste that I should be heartily glad to show it to you.”

Downing advised Cora’s husband, Thomas Barton, in a letter of 1850, “I send Mr. Barton two notes. I think on the whole Whitely and Thomes[?] is the best collection of rare trees abroad & I am particularly pleased with the botanical knowledge of that firm & its great promptness & punctuality in executing orders. Rivers Nursery stands at the head for fruit trees & roses–with many other fine things…. The best grass is the Kentucky blue grass–2 bushels to the acre.” (Photo: Montgomery Place/Barbara Israel)

Even the ornaments that were purchased for the gardens at Montgomery Place carry the Downing imprimatur. After Downing’s death in 1852 his influential periodical The Horticulturist continued to offer knowledge and advice about the landscape. An 1857 article titled “Terra Cotta Ornaments” recommended an Italian artist called Ambrose Tellier who had recently arrived in New York [The Horticulturist 7-Feb 1857]. Quite a few years ago I had the privilege of inspecting the terra cotta ornament collection at Montgomery Place and was amazed to find that particular artist’s name on some pieces. (Montgomery Place Terra Cotta/Barbara Israel)

Even the ornaments that were purchased for the gardens at Montgomery Place carry the Downing imprimatur. After Downing’s death in 1852 his influential periodical The Horticulturist continued to offer knowledge and advice about the landscape. An 1857 article titled “Terra Cotta Ornaments” recommended an Italian artist called Ambrose Tellier who had recently arrived in New York [The Horticulturist 7-Feb 1857]. Quite a few years ago I had the privilege of inspecting the terra cotta ornament collection at Montgomery Place and was amazed to find that particular artist’s name on some pieces. (Montgomery Place Terra Cotta/Barbara Israel)

The Hudson Valley was fortunate to have such significant 19th-century architects and designers find their callings by working on its houses and grounds. These specialists–particularly Downing–benefited from their proximity to the extraordinary confluence of abundant land, remarkable topography and a majestic river.

The Father of American Landscape Architecture

By Eva Schwartz

“It cannot be denied that the tasteful improvement of a country residence is both one of the most agreeable and the most natural recreations that can occupy a cultivated mind. With all the interest and, to many, all the excitement of the more seductive amusements of society, it has the incalculable advantage of fostering only the purest feelings, and (unlike many other occupations of business men) refining, instead of hardening the heart.

–Andrew Jackson Downing The Horticulturist, and Journal of Rural Art and Rural Taste, Vol III, No. I, July 1848

It is widely acknowledged among historians that landscape architecture did not become a real profession in the United States until Andrew Jackson Downing (1815-1852) had the vision to make it so. He learned practical planting know-how at his family’s nursery, but he was much more than an expert on botanical species; he was a tastemaker of the highest order, who did more to influence the way Americans designed their properties than anyone else before or since. He was intensely devoted to New York State’s Hudson Valley, making his home in Newburgh, working for clients in the area, and writing on trees and plants of the region. He was committed to the creation of an inherently American style of landscape design–one that heavily favored native plants and trees and celebrated its diverse natural wonders. Most importantly, Downing was the first to articulate the now-common democratic ideals of landscape design–that parks should be accessible to everyone and that they should contribute to the general uplifting of society. It is almost hard to imagine it now, but in the mid-19th century, Downing’s ideas were revolutionary–and they would forever change the way Americans thought about their outdoor spaces. (Photo: Frontispiece portrait of Andrew Jackson Downing from A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, 1853/G. P. Putnam, Publisher, Wikimedia Commons).

It is widely acknowledged among historians that landscape architecture did not become a real profession in the United States until Andrew Jackson Downing (1815-1852) had the vision to make it so. He learned practical planting know-how at his family’s nursery, but he was much more than an expert on botanical species; he was a tastemaker of the highest order, who did more to influence the way Americans designed their properties than anyone else before or since. He was intensely devoted to New York State’s Hudson Valley, making his home in Newburgh, working for clients in the area, and writing on trees and plants of the region. He was committed to the creation of an inherently American style of landscape design–one that heavily favored native plants and trees and celebrated its diverse natural wonders. Most importantly, Downing was the first to articulate the now-common democratic ideals of landscape design–that parks should be accessible to everyone and that they should contribute to the general uplifting of society. It is almost hard to imagine it now, but in the mid-19th century, Downing’s ideas were revolutionary–and they would forever change the way Americans thought about their outdoor spaces. (Photo: Frontispiece portrait of Andrew Jackson Downing from A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, 1853/G. P. Putnam, Publisher, Wikimedia Commons).

It is fair to say that Downing owed a great deal to the philosophies of Britain’s naturalists–Lancelot “Capability” Brown (1716-1783), Humphry Repton (1752-1818) and John Claudius Loudon (1783-1843). Capability Brown–given his nickname as he was famous for telling clients that their properties had “capability for improvement”–is largely given credit for developing the naturalistically styled English Landscape Garden. After working under the tutelage of the renowned architect/designer William Kent, Brown was responsible for the widespread acceptance of the new style of landscape design, which came as a direct challenge to the Italian and French-influenced formal schemes that had been the norm. Brown, who called himself a “Place Maker”, not a landscape designer, designed over 170 parks and gardens, all of which were carefully planned to look as “natural” as possible, making use of vast lawns, clumps of expertly placed trees, serpentine lakes and long vistas. His style was the “gardenless” form of landscape gardening, painstakingly engineered with the conceit that it not look at all planned.

Humphry Repton and John Claudius Loudon, considered Brown’s successors, were prolific writers whose treatises Downing ardently studied. They were Brown’s followers in a general sense, but were also great innovators. In response to Brown’s sweeping lawns that would run right up to the house, Repton reintroduced formal touches to the landscape–flower gardens, balustrades, terraces, all of which were kept close to the house as a natural continuation of the architecture. This idea of keeping formal elements in close proximity to the main house–and using ornament that would echo the architecutral style of that structure–was hugely influential and became a cornerstone of Downing’s theories as well. John Claudius Loudon, the Scottish botanist, garden designer, author, and magazine editor who popularized the term “landscape architecture” was perhaps Downing’s strongest influence. A self-described city planner, Loudon was a fervent supporter of accessible green spaces in urban environments (see his 1829 book Hints on Breathing Places for the Metropolis)–a subject that was dear to to Downing’s heart.

Downing certainly modeled himself after Loudon, harnessing the power of print to disseminate his own theories of landscape architecture. He was only 26 years old when he published the incomparable work, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, Adapted to North America, (1841). This book–part practical planting advice, part philosophy, part rallying cry–was the first of its kind in the United States and is still considered the most influential ever published. Before this treatise, wealthy landowners dabbled in landscape design as a hobby; Downing made it a venerable profession and something that a person of lesser means could become. In it Downing described the proper use of ornament, the varieties of trees and other native plants and how they were best employed, the importance of coherent design, as well as distinguishing the principles of the Picturesque and the Beautiful with regard to landscape architecture. (Image: A drop cap illustration from A Treatise…, Fourth Edition, 1852, p. 85)

Downing certainly modeled himself after Loudon, harnessing the power of print to disseminate his own theories of landscape architecture. He was only 26 years old when he published the incomparable work, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, Adapted to North America, (1841). This book–part practical planting advice, part philosophy, part rallying cry–was the first of its kind in the United States and is still considered the most influential ever published. Before this treatise, wealthy landowners dabbled in landscape design as a hobby; Downing made it a venerable profession and something that a person of lesser means could become. In it Downing described the proper use of ornament, the varieties of trees and other native plants and how they were best employed, the importance of coherent design, as well as distinguishing the principles of the Picturesque and the Beautiful with regard to landscape architecture. (Image: A drop cap illustration from A Treatise…, Fourth Edition, 1852, p. 85)

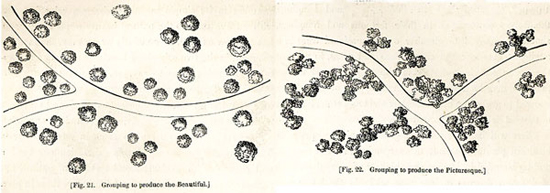

In practical terms Picturesque elements were irregular, jagged, and as Downing put it, “spirited”, while Beautiful ones were regular, graceful, smooth, and gently rounded. An example of the Picturesque would be a cragged pine tree leaning over a rocky cliff; the Beautiful would be a stand of stately American Elm trees on an expanse of grass. Downing’s ideal landscape combined both types of plantings to create a uniquely Romantic vision. (Image: Tree groupings illustrating the Beautiful, Fig. 21, and the Picturesque, Fig. 22, from A Treatise…, Fourth Edition, 1852, pp. 102-103)

Downing’s ideas of aesthetics stemmed from the Romantic movement that dominated artistic output from the late 18th century to the mid 19th century in Europe and America, encompassing fine art, literature, music and philosophy. Like landscape painters of the period, he believed that nature should be elevated and interpreted, not slavishly copied. In the Treatise Downing stressed that “By Landscape Gardening, we understand not only an imitation…of the agreeable forms of nature, but an expressive, harmonius, and refined imitation [italics his]. In Landscape Gardening, we should aim to separate the accidental and extraneous in nature, and to preserve only the spirit, or essence.” So when designing a rural property, this meant creating lakes, ponds, knolls and hills where they hadn’t existed, planting trees and removing them when they blocked a view, installing a serpentine drives so as to add intrigue–all contributing to a landscape that was engineered to elevate the natural world. (Photo: Pond at Montgomery Place/Barbara Israel)

Downing’s ideas of aesthetics stemmed from the Romantic movement that dominated artistic output from the late 18th century to the mid 19th century in Europe and America, encompassing fine art, literature, music and philosophy. Like landscape painters of the period, he believed that nature should be elevated and interpreted, not slavishly copied. In the Treatise Downing stressed that “By Landscape Gardening, we understand not only an imitation…of the agreeable forms of nature, but an expressive, harmonius, and refined imitation [italics his]. In Landscape Gardening, we should aim to separate the accidental and extraneous in nature, and to preserve only the spirit, or essence.” So when designing a rural property, this meant creating lakes, ponds, knolls and hills where they hadn’t existed, planting trees and removing them when they blocked a view, installing a serpentine drives so as to add intrigue–all contributing to a landscape that was engineered to elevate the natural world. (Photo: Pond at Montgomery Place/Barbara Israel)

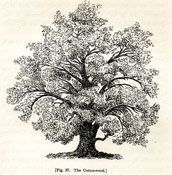

Of course, the natural splendor of the Hudson Valley region provided endless inspiration, and not just to Downing. It was the stomping ground of many Romantic thinkers and artists of the time, including the great Hudson River School painters. One of those was Frederic Church, whose Olana estate in Hudson, NY is one of the most stunning examples of Romantic architecture ever built. The internationally renowned author Washington Irving made his home in Tarrytown in 1846. His estate, Sunnyside, is a formidable example of American landscape design, and Irving himself was the architect and visionary. Downing visited Sunnyside as a young man and later professed its virtues in his writings. Irving’s skill in situating the house in the grounds, and developing a plan that exploited both the magnificent view of the Hudson along with creating garden walks and secluded hideaways was a benchmark in American landscape gardening and one that was emulated in the decades to come. (Image: Fig. 37, The Cottonwood, from A Treatise…, Fourth Edition, 1852, p. 177)

Of course, the natural splendor of the Hudson Valley region provided endless inspiration, and not just to Downing. It was the stomping ground of many Romantic thinkers and artists of the time, including the great Hudson River School painters. One of those was Frederic Church, whose Olana estate in Hudson, NY is one of the most stunning examples of Romantic architecture ever built. The internationally renowned author Washington Irving made his home in Tarrytown in 1846. His estate, Sunnyside, is a formidable example of American landscape design, and Irving himself was the architect and visionary. Downing visited Sunnyside as a young man and later professed its virtues in his writings. Irving’s skill in situating the house in the grounds, and developing a plan that exploited both the magnificent view of the Hudson along with creating garden walks and secluded hideaways was a benchmark in American landscape gardening and one that was emulated in the decades to come. (Image: Fig. 37, The Cottonwood, from A Treatise…, Fourth Edition, 1852, p. 177)

It is important to discuss Sunnyside in relation to Downing–despite the fact that he was not responsible for its design–because, tragically, there are almost no surviving Downing landscapes. (See accompanying aricle in this issue on one of those rare extant properties, called Springside, in Poughkeepsie, NY.) Thus it is meaningful to study Sunnyside as a representation of the ideals that Downing championed. As noted by Robert M. Toole in the Journal of Garden History, “…the size and scale of Sunnyside spoke to the aspirations of a broader range of people who could not afford large estate properties. Sunnyside was a tangible example of the modest, American, ‘democratic’ homes and landscapes that had special interest for A. J. Downing and would have special relevance for the future.” (1992, vol. 12, no. 1, p. 59)

Montgomery Place, a nearby property in Annandale-on-Hudson, is representative of Downing’s principles at their finest. Though Downing did not officially design the gardens at Montgomery Place, he was a close friend of owners Cora and Thomas Barton. Cora, nee Livingston, had grown up on the great estate of Clermont, the seat of the powerful Livingston family. Downing was still a

young nurseryman when they met, and sold the Bartons quite a few specimens of trees and plants. He was a regular visitor to Montgomery Place and was the Bartons’ trusted advisor in the matter of landscape design and planting. When, in 1846, Downing became the editor-in-chief of the widely-read, trendsetting magazine The Horticulturist, and Journal of Rural Art and Rural Taste, he chose Montgomery Place as the estate that best illustrated the American Rural ideal. And Downing intended that Ideal to inspire and guide his readers in their own gardens, however modest they might have been. (Photo: Garden at Montgomery Place and View from the Entrance of Montgomery Place/Barbara Israel)

One of Downing’s early partners in landscape design was Calvert Vaux, who went on after Downing’s death to design Central Park with Frederick Law Olmsted. Both Vaux and Olmsted were deeply influenced by Downing’s personality and his work, and lobbied for a monument in the park commemorating him, stating that it would be an “appropriate acknowledgment of the public indebtedness to the labors of the late A. J. Downing, of which we feel the Park is one of the direct results.” Indeed, it was Downing, long before Olmsted, who tirelessly campainged for Central Park, insisting that more than 800 acres be set aside instead of the 60 that were at first approved by city planners. In Rural Essays, Downing argued that “the taste of an individual, as well as that of a nation, will be in dierct proportion to the profound sensibility with which he perceives the beautiful in natural scenery. Open wide, therefore, the doors of your libraries and picture galleries all ye true republicans! Build halls where knowledge shall be freely diffused among men, and not shut up within the narrow walls of narrower institutions. Plant spacious parks in cities, and unclose their gates as wide as the gates of morning to the whole people.” (Photo: A. J. Downing Memorial Urn/Ser Amantio di Nicolao, Wikimedia Commons)

One of Downing’s early partners in landscape design was Calvert Vaux, who went on after Downing’s death to design Central Park with Frederick Law Olmsted. Both Vaux and Olmsted were deeply influenced by Downing’s personality and his work, and lobbied for a monument in the park commemorating him, stating that it would be an “appropriate acknowledgment of the public indebtedness to the labors of the late A. J. Downing, of which we feel the Park is one of the direct results.” Indeed, it was Downing, long before Olmsted, who tirelessly campainged for Central Park, insisting that more than 800 acres be set aside instead of the 60 that were at first approved by city planners. In Rural Essays, Downing argued that “the taste of an individual, as well as that of a nation, will be in dierct proportion to the profound sensibility with which he perceives the beautiful in natural scenery. Open wide, therefore, the doors of your libraries and picture galleries all ye true republicans! Build halls where knowledge shall be freely diffused among men, and not shut up within the narrow walls of narrower institutions. Plant spacious parks in cities, and unclose their gates as wide as the gates of morning to the whole people.” (Photo: A. J. Downing Memorial Urn/Ser Amantio di Nicolao, Wikimedia Commons)

When Downing died tragically in a steamship accident in 1852, he was mourned across the nation. A marble urn was erected on the Washington Mall in 1856 to celebrate his legacy [visit it today at the Enid Haupt garden near the Smithsonian castle]. The inscription reads: “He was born, and lived, and died upon the Hudson River. His life was devoted to the improvement of the national taste in rural art, an office for which his genius and the natural beauty amidst which he lived had fully endowed him”.

To learn more about Sunnyside or Montgomery Place, now operated by Historic Hudson Valley, visit www.hudsonvalley.org.

Springside: The Last Extant Property by A. J. Downing

By Katy Keiffer

The last example of Andrew Jackson Downing’s work is Springside, the 20-acre estate in Poughkeepsie, NY, created for Matthew Vassar, the founder of Vassar College. Springside was intended to be part leisure estate and part working farm. In addition to the landscape, the buildings were also designed by Downing in 1850-51, with some assistance from Calvert Vaux, the architect he had brought over from England and with whom he worked until his death in 1852.

Taking advantage of the stunning natural elements of the landscape, Downing’s design combined his principles of the Picturesque and the Beautiful by means of an elaborate infrastructure that was invisible to all but those privy to the original plans. Thousands of trees were transplanted, and multiple streams were diverted, or dug, to power the many water features that accessorized the overall landscape. At right is Andrew Jackson Downing’s original 1851 landscape plans for Springside. (Source: Vassar College Encyclopedia/Daniel Case, Wikimedia Commons)

Taking advantage of the stunning natural elements of the landscape, Downing’s design combined his principles of the Picturesque and the Beautiful by means of an elaborate infrastructure that was invisible to all but those privy to the original plans. Thousands of trees were transplanted, and multiple streams were diverted, or dug, to power the many water features that accessorized the overall landscape. At right is Andrew Jackson Downing’s original 1851 landscape plans for Springside. (Source: Vassar College Encyclopedia/Daniel Case, Wikimedia Commons)

The estate had been a working farm, and gardens and orchards had been already laid out. Vassar added a number of elements to augment the “farm” aspect of the property, including a large aviary, an apiary, a greenhouse and grapery, and a dairy. All of the buildings were built in the same board and batten Gothic Revival style favored by Downing. The mansion originally conceived for the property was never built as Vassar was content to stay in the “gardener’s cottage”.

The estate had been a working farm, and gardens and orchards had been already laid out. Vassar added a number of elements to augment the “farm” aspect of the property, including a large aviary, an apiary, a greenhouse and grapery, and a dairy. All of the buildings were built in the same board and batten Gothic Revival style favored by Downing. The mansion originally conceived for the property was never built as Vassar was content to stay in the “gardener’s cottage”.

Following Vassar’s death in 1868, subsequent owners of Springside kept the house and grounds almost exactly as it had been since its inception, but by the mid 20th century the property had fallen into disrepair. There was a great deal of pressure to develop the land, build a school, or otherwise dismantle the estate. These plans were finally derailed by local preservationists who succeeded in having the site made a National Historic Landmark in 1969. (Photo: Landscape near former cottage site at Springside/Daniel Case, Wikimedia Commons)

Of all the structures, only the Gatehouse remains standing, with the original sandstone walls, columns and wrought-iron gates in front. Happily, Springside has been undergoing major renovations in the last few decades. In its heyday, Spingside was considered one of the most beautiful of the Hudson Valley properties, and during his lifetime Vassar frequently opened the grounds to the public for their enjoyment. As one visitor remarked at the time, “…a more charming spot we never have visited. There is combined within these precincts every variety of park-like and pictorial landscape that is to be found in any part of our country–meadows, woodlands, water-sources, jets and fountains, elevated summits gently sloping into valleys…” (Source: Vassar College Encyclopedia)

Of all the structures, only the Gatehouse remains standing, with the original sandstone walls, columns and wrought-iron gates in front. Happily, Springside has been undergoing major renovations in the last few decades. In its heyday, Spingside was considered one of the most beautiful of the Hudson Valley properties, and during his lifetime Vassar frequently opened the grounds to the public for their enjoyment. As one visitor remarked at the time, “…a more charming spot we never have visited. There is combined within these precincts every variety of park-like and pictorial landscape that is to be found in any part of our country–meadows, woodlands, water-sources, jets and fountains, elevated summits gently sloping into valleys…” (Source: Vassar College Encyclopedia)

Springside is open to the public and offers self-guided tours, as well as a wealth of beautiful trails, winding paths, and “natural rooms” created by the vision of Downing’s plantings. Guided tours can also be arranged by calling the estate. For more information visit: www.springsidelandmark.org.

———————–

Our next Focal Points will be devoted to little-known or difficult to visit gardens, one being the Japanese Garden at Kykuit in Pocantico, NY.