Lyndhurst

By Barbara Israel

When I agreed to do an antiques show at Lyndhurst I had little idea what added sights would be in store for me. I knew very well that it was a National Trust Property in Tarrytown, NY and that the Director, Howard Zar, had accomplished a major turn around in his five years on the job. I’d been there once to view their statuary collection in a dark basement vault near the greenhouses but had never been in the mansion.

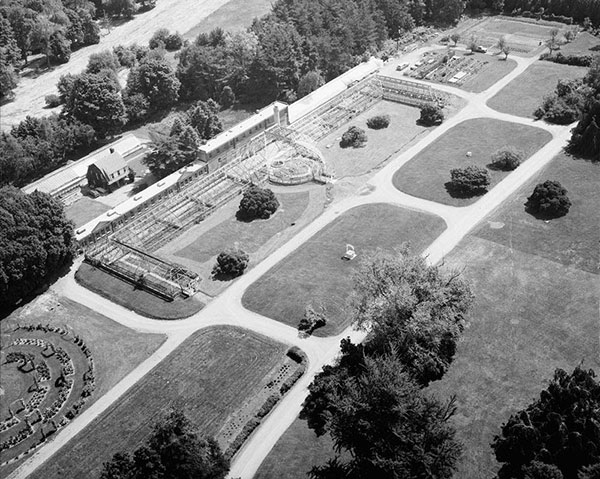

We participants of “Antiques on the Hudson”, which was presented in tandem with the April 7th-8th opening weekend of Lyndhurst Mansion and its “Spring Blossoms” flower show, were set up were set up in a tent in the courtyard of the Carriage House some distance from the main house (above). On Saturday three friends arrived to see the antiques show and Howard offered to give us a tour. That tour turned out to be a few hours passing under velvet ropes that revealed the unseen but soon to be public rooms. We peered through the doors of the minstrel’s gallery and looked down at the painting collection (below).

Hearing a number of owners’ names mentioned during the tour I realized that one needs some explanation to understand Lyndhurst’s ownership history:

1836 Bought by William Paulding, Jr. (1770-1854) and his son Philip (1816-1864)

1864 Philip sold it to George Merritt (1807-1873)

1880 Jay Gould (1836-1892) bought it from the Merritt family

1892 Helen Gould (1868-1938), Jay’s daughter, took over and in 1898 bought out her siblings

1938 Duchess of Talleyrand-Perigord, Anna Gould (1875-1961), Helen’s younger sister took it over

1961 Anna’s will bequeathed Lyndhurst to the National Trust

This amazing 184-acre piece of land overlooking the Hudson had been part of the Requa Farm when its first owner, William Paulding, Jr. bought it in 1836. In 1838 he hired a distinguished architect, Alexander Jackson Davis (1803- 1892), to design an appropriate house for him. The Gothic Revival mansion, known as the “pointed style”, is considered Davis’ masterpiece work and exists today with only minor changes. By a stroke of good luck the second owner, George Merritt, rehired Davis to expand the house in 1864-65 and doubled the size adding a five-story Tower, the North wing and a large porte-cochere. Thus, the extant mansion, now on 67 acres, is entirely the work of a single architect.

A similar circumstance transpired with the landscape. In the 1860s Mr. Merritt, who was passionate about plants and gardens, engaged Ferdinand Mangold (1828-1905) to lay out the parkland surrounding the house and he remained as the gardener until his death, having worked for both the Merritts and the Goulds. The initial job was extensive as Mr. Mangold had to drain the swampland in order to create the level, dry open spaces that his training in the “gardenesque” style required. The proponent of this garden style was the Scotsman, John Claudius Loudon (1783-1843) who found the strictly naturalistic gardens of the 18th century lacking by not revealing the artful work underlying the project. In 1832 he introduced “gardenesque” that combined the openness of a romantic garden while employing occasional geometric patterns from the formal Italianate style. [Above: Aerial view of Greenhouses and Gardens, Looking Northeast. Public Domain: Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, HABS NY, 60-TARY, 1B–12, Creator – Jack E. Boucher, 1971]

Loudon had also popularized the use of greenhouses with hinged windows that could regulate airflow and under Mangold’s careful eye Merritt installed a vast greenhouse measuring 390 ft. It was one of the largest privately owned greenhouses in the country at the time. Mangold also planted many specimen trees, which have survived to become monumental in some cases.

In 1880 just as Jay Gould had purchased Lyndhurst the greenhouse burned down but in 1881 Gould replaced it with a Gothic style Lord and Burnham cast-iron and steel version of similar scale. Lord and Burnham were a local company based in Irvington, NY who also constructed the Edith Haupt Conservatory at the New York Botanical Garden in the Bronx. [Above: Photocopy of Old Photograph, General View of Exterior, Undated. Public Domain: Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, HABS NY, 60-TARY, 1B–19, Creator – Jack E. Boucher, 1971.]

Currently, the vast project facing Lyndhurst is the restoration of their greenhouse. At this point the enormous metal structure still proudly stands on the property but without a trace of glass in it. The National Trust stored the glass and various wood and metal elements when they took it over after 1961. The glass would have to be brought up to code but it remains entirely possible to re-create the extraordinary structure as it existed from the 1880s until the 1960s.

When Helen Gould took over the property she established a Rose Garden in a circular pattern to the west of the greenhouses. In the center she placed an ornate wellhead with an overthrow that is now in front of the greenhouses. Her sister, Anna, later replaced it with a stone and wrought-iron gazebo and moved the wellhead to where it is now. I saw the unrestored wellhead on my first visit to Lyndhurst (far right) so was very happily surprised to see it now after extensive conservation. (right).

Back to our tour… it took us up all five stories to the top of the tower from which we could see the Tappan Zee Bridge. An unprepossessing room at the top of the tower served as an extra bedroom. It was easy to understand the landscape from that high up and notice the massive specimen trees dotting wide swaths of lawn that Ferdinand Mangold had laid out. Another of Helen Gould’s changes after her father died was to gradually add a number of outbuildings, some of which we could see from the tower: the bowling alley, the laundry house, the kennels, an indoor swimming pool, and a playhouse called Rose Cottage.

The Gothic style of the house with its many stained glass windows is very different than the usual interiors of the grand houses on the Hudson. Most of the original furniture, some of it designed by Alexander Jackson Davis himself, still enhances the halls, living rooms, dining room, and library. When George Merritt was the owner he encouraged Davis to add colored trims and faux finishes to the ceilings (right) to achieve more extravagant design elements in the downstairs rooms.

In the main house after seeing all the beautifully restored public rooms we got to visit the kitchen that is soon to be opened to the public. The basement contains the old icehouse (left), a remarkably dark, eerie space oozing water from the walls. We ventured out of the main house to the cottage just to the north where we saw the laundry on the lower level with all the old drying racks on slides, the mangles, and the multitude of sinks. All the rooms seemed entirely authentic and well preserved.

In the main house after seeing all the beautifully restored public rooms we got to visit the kitchen that is soon to be opened to the public. The basement contains the old icehouse (left), a remarkably dark, eerie space oozing water from the walls. We ventured out of the main house to the cottage just to the north where we saw the laundry on the lower level with all the old drying racks on slides, the mangles, and the multitude of sinks. All the rooms seemed entirely authentic and well preserved.

Afterward I walked the property to take in the few ornaments that remain on display in the park. A lovely classical bronze stands to the south of the house looking up to the floors above (below, left). The signature identifies it as being by Sherry Edmundson Fry (1879-1966), an American sculptor from Iowa.

On the way to the Carriage House (where there was a café in the old stable–the horse stalls have been cleverly made into booths) near Rose Cottage, is a strange square wellhead (far right) with three ornamented sections on each side. I can only guess that it could be something that Anna, the last Gould owner, might have imported from France where she had lived. Its size makes me think it was originally in a civic location, perhaps in a village or town square.

Just over a few hours on Saturday I had discovered the many stories of an extraordinary house and property. Our tour guide, the Director himself, has brought it up to the standard of all the houses along the Hudson that have entranced me for years. It is a wonderful tour and visit that will only improve week by week as more and more of the “downstairs” rooms are opened.

Thanks to Great Houses of the Hudson River, edited by Michael Middleton Dwyer, New York: Bullfinch Press, 2001.

By way of explanation, as a dog lover I had to include this favorite canine-centric embellishment (above).

The Robert Wood Foundry and the Allure of Cast Iron

By Eva Schwartz

I guess you could say I’m a cast-iron geek. I mean, it’s not something I ever planned on being. But when I came to work for Barbara in 1997, at first as a research assistant for Barbara’s 1999 book, Antique Garden Ornament: Two Centuries of American Taste, I developed a fascination with the material. For one thing, cast iron represented innovation and the possibilities of industry. Design-wise, it could be anything you wanted it to be, and could be produced faster and more efficiently than carved stone. From the 1860s through the 1890s—what we’d call the Golden Age of cast-iron ornament—foundry catalogs were brimming with varied, inventive offerings. And the general affordability of the items therein meant that just about anyone could purchase something beautiful for their home or garden. [Image: Chase Brothers catalog, Boston, 1861-62.]

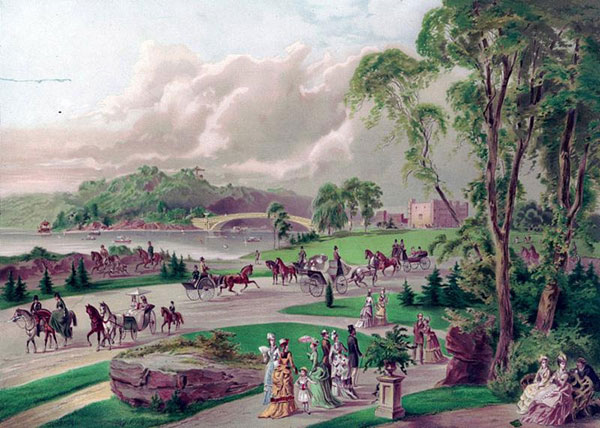

I found this simple idea—that everyone should be able to own art or ornaments—remarkably appealing. Moreover, it made sense that the popularity of cast-iron ornament coincided with this particular period in American history, when the idea of making green spaces accessible to all had at last gained widespread support (Central Park, one of the most storied of those spaces, first opened in 1858). Additionally, a nascent middle class meant that more people had gardens and leisure time, kicking off a national interest in gardening and garden ornament that thrives to this day. Not that cast iron didn’t have plenty of critics, especially by the turn of the 20th century, when the material was deemed déclassé. By that point, the affordability of cast-iron ornaments meant that some consumers had, perhaps, indulged in the “more is more” line of thinking a bit too often! One of the more opinionated art critics of the day, Samuel Swift, a regular contributor to House and Garden magazine in the early 20th century, despised the cast-iron animals that had proliferated on American lawns. In “American Garden Pottery” (House and Garden, August 1903), he argued that to have moved on from the era of cast-iron ornaments was to have greatly improved public taste. [Image credit: Library of Congress]

I can understand Swift’s thinking. An aesthete by any measure, he was no doubt dismayed by the mass-manufacturing, mass-marketing characteristics of cast-iron ornament production. But, thankfully, time has a way of elevating even the most disparaged aspects of any historical era; we can’t help but gain perspective. In my case, growing up in a household where the standards of mid-20th-century design reigned, my distaste for Victorian decorative arts was preordained—until, of course, I studied the period in graduate school. It’s true about so many things—when you learn more, your enthusiasm grows. Suddenly, I appreciated the industrial advancements of the age, the penchant for far-flung, eclectic design sources, the open-mindedness about materials, the genius for marketing and the value of making art affordable for all. Is it any wonder I got hooked on this stuff?

As with any industry, production quality varied from foundry to foundry. It would be hard to beat the sophisticated designs (above) of Janes, Beebe & Company (New York, active 1847-1933 under various business names), or the fine selection of urns (right) by William Adams (Philadelphia, active 1872 to 1929 under varying names), to mention just two of the top-notch firms. As antique dealers in New York, we’re admittedly biased toward the New York makers (most notably, J.W. Fiske and J.L. Mott Iron Works), but anyone knowledgeable about cast iron knows that the heart of the industry was really in Philadelphia. So, in honor of our participation in the Philadelphia Antiques Show (April 20th-22nd), I thought it fitting to turn my attention to Philadelphia’s cast-iron industry and to the most prolific of all its foundries, Robert Wood.

To set the stage: Philadelphia’s cast-iron dominance was largely due to Pennsylvania’s anthracite coal deposits—and the fact that anthracite coal burned much longer and more efficiently than bituminous coal (which had been the standard in other areas of the country), allowing for vastly increased production of industrial materials, including cast iron. Equally important to the success of the cast-iron industry was Philadelphia’s position as a railroad and shipping hub, with access to several important waterways.

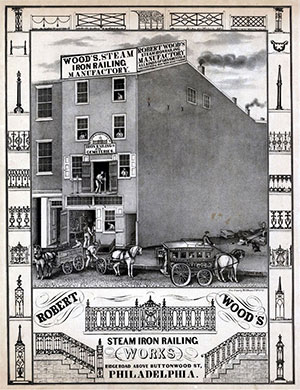

The Philadelphia blacksmith and iron founder, Robert Wood, established his business on Ridge Road in 1840 (sadly, no longer standing). At first he produced stoves, pipes, and other utilitarian objects, but by 1850, decorative ornaments had been added to the mix—and it was in the manufacture of these pieces that Wood excelled. In 1850, O’Brien’s City Directory proclaimed the firm to be “one of the most prominent features of the . . . flourishing city . . . Strangers who visit Philadelphia are frequently shown Mr. Wood’s establishment, among other lions of that city, such as Independence Hall and Laurel Hill”. The Directory also reported that Robert Wood was producing at least 150 designs for ornamental railings, along with verandah components, pier and center tables, settees, chairs, hat and umbrella stands, tree boxes and bedsteads. In that year, the decorative output was mainly comprised of architectural wares and interior furnishings. The company had yet to venture earnestly into garden ornament production.

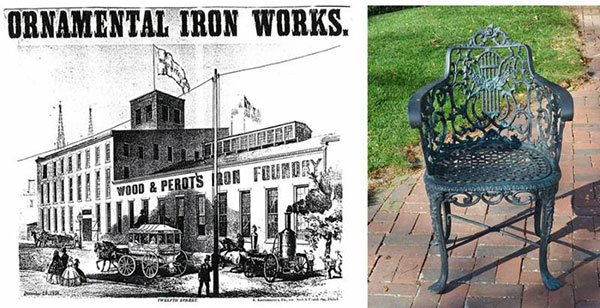

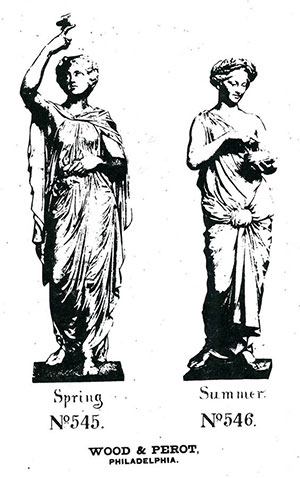

By 1858, Robert Wood had partnered with Elliston Perot, and was operating as Wood & Perot. The Wood & Perot period (1858-1866)—relatively short in the life of the company—saw an explosion in the way of ornamental offerings and an expansion of the firm well beyond the Philadelphia metropolitan area. The production of garden objects increased dramatically, with a broader range of settees, planters, animal and figural statuary, fountains, freestanding pavilions and cemetery furnishings. Many of the designs in the 1858 catalog are copies of English and French patterns, but a few, including the well-known “lyre-back” armchair (above right) seem not to have had European precedents. The catalog offerings practically burst off the page owing to the number and variety of designs, and the intricate line drawings speak to the refined quality of the work.

Image credit: Karl Gildemeister (1880-1869) – New York Crystal Palace at beinecke.library.yale.edu

Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/2/index.php?curid=4529897

Of course, quality and attention to detail had been hallmarks of Robert Wood’s work even before Elliston Perot came on board. An 1854 publication, The Industry of the United States in Machinery, Manufactures, and Useful and Ornamental Arts, a compilation of reports written by two British Commissioners, Sir Joseph Whitworth (1803-1887) and George Wallis (1811-1891), named Robert Wood’s establishment as one of the finest in the nation and on par with the best in the world. The two Englishmen had been sent to observe and report on New York’s 1853 Crystal Palace exposition, known formally as the Exhibition of the Industry of All Nations, but their reporting took them much farther than New York. Indeed, a casual flip through the book will leave you wondering how long it must have taken to visit all the button factories in Tennessee and “pocket-cutlery” outfits in Connecticut! Wallis’ background was in art, having served as headmaster of some of Britain’s most prestigious art and design schools, one of which was devoted to the design of firearms, so he had a sense of industry as well. Indeed, he went on to be one of the top “keepers” at the South Kensington Museum (later renamed the Victoria & Albert), an institution known for both its decorative arts and industrial works. Wallis’ lifelong friend, Whitworth, was a successful engineer and inventor, known for designing lathes and other mechanical tools.

Credits: Left – The Library Company of Philadelphia; Right – By James Fuller Queen, 1820/21-1886, artist; P.S. Duval &Co., printer, Library of Congress Catalog, http://lccn.loc.gov/2014649375

Both Wallis and Whitworth had extensive experience in the applied arts, and had participated in London’s Crystal Palace Exhibition in 1851, so they were well-positioned to assess the state of arts and manufacturing in America. Thus, their praise of American industry, and particularly of the ornamental iron foundries of Philadelphia, carried significant weight. They were especially impressed with Robert Wood’s production, making note of the “ornamental castings for architectural purposes”, but also highlighting the “garden decorations” that were “superior” in design and quality. [Mentioned as well is a 15-foot tall statue of Henry Clay, commissioned by citizens of Pottsville, PA. As a U.S. Senator, Henry Clay had pushed for tariffs in favor of the coal companies in Western Pennsylvania and the iron founders in Philadelphia, so he was a hero in those parts. Wood & Perot ended up casting one Henry Clay statue for Pottsville, and another to grace the roof of their Ridge Road factory.] Wallis and Whitworth’s report apparently caused such a stir back in England that it warranted some pointed remarks by the great John Bright (1811-1889) on the floor of the House of Commons (cited by The Athenaeum Journal of Literature, Science, and the Fine Arts for the Year 1854, London):

There are many things in Mr. Whitworth’s report which have startled manufacturers and men of science in this country. He has shown that in certain departments there is an increasing skill and knowledge which threatens not only to rival, but to excel anything existing in this country.

Another contemporary appraisal of Philadelphia manufacturing, Philadelphia and its Manufactures: A Hand-Book Exhibiting the Development, Variety, and Statistics of the Manufacturing Industry of Philadelphia in 1857, Together with Sketches of Remarkable Manufactories; And a List of Articles Now Made in America, by Edwin T. Freedley, published in 1859, also sung the praises of Philadelphia iron work. Freedley notes that “most of the cemeteries and public squares throughout the whole country are adorned by work executed in Philadelphia; and every city, probably every town in the Union, contains some specimen of our manufacturers’ skill and trade”. It’s worth noting that, while there may have been some exaggeration, this statement was certainly more true than not, owing to Philadelphia’s dominance in the decorative iron trade at that time. [Credit: The Library Company of Philadelphia.]

Freedley was especially impressed by the Wood & Perot manufactory. He devotes several pages to the firm, marveling at how much the enterprise had grown, both in importance and influence, but also physically, as the factory had gotten ever larger. At the time of Freedley’s writing, “a row of tenements on Twelfth Street was purchased and torn down, to give place to a new foundry eighty feet square, and . . . thus this manufactory has gone on extending and absorbing other buildings, until now it . . . occupies almost the entire square bounded by Ridge Avenue, Twelfth, Spring Garden, and Buttonwood Streets”. Freedley makes particular note of the role Robert Wood (and Perot) had played in making art attainable for all. [Image: Stereographic view of the Philadelphia garden of J.R. Evans, ca. 1861. Credit: The Library Company of Philadelphia.]

He fondly recalls the significance of Robert Wood’s first illustrated catalog:

It was then seen, as we believe for the first time, that forms of rare artistic beauty in an imperishable material were within the reach of men of very moderate means. The farmer, as well as the millionaire, could have an ornamental verandah , decorations for his garden or his grounds, and a beautiful iron protection around the graves of his ancestors; and thus one barrier to the equality of mankind was removed. The chasm that separates rural towns from the great cities was also narrowed, and objects of high Art were no longer confined exclusively to the latter, but became diffused and familiar in both, alike educating the taste of the people, and promoting public spirit and private content.

Reading that passage makes me think I would have gotten along quite well with Mr. Freedley as I’d felt those things, too, about cast iron. Perhaps the best section of Freedley’s Wood & Perot write-up, though, is the long excerpt quoted from the Evening Bulletin, Philadelphia’s largest newspaper at the time. The Bulletin reporter, having just visited the foundry buildings, was clearly taken by the experience:

The visitor is first ushered into the show rooms on the second floor, on Ridge Avenue, and he finds himself among . . . men, women, stags, lions, dogs, lambs, eagles, etc., etc., faithfully reproduced in iron, and some of the objects are modeled so truthfully and so naturally, that they have not unfrequently [sic] been taken forthe living animals they represent. In this apartment a graceful iron fountain throws refreshing jets into the air, while in the basin at its foot gold fish swim among cast iron bull-frogs, and it requires a keen sight to detect that the latter are not the living animals they seem. . . Not only is there an immense variety in the objects displayed, but the visitor becomes bewildered among the almost infinite variety of patterns the different articles are made to assume.

The reporter remarks on the vast number of orders the foundry was filling for clients both near and far. The Custom House in Oswego, NY, was getting a new iron railing, as was the Patent Office in Washington, D.C., and they’d already shipped a complete mausoleum to a client in New Orleans. Luckily, these pieces were produced in components that shipped relatively flat in wooden boxes (the IKEA of its day!). Indeed,

They are constantly receiving and filling orders for ornamental iron work for all parts of the United States, and for Cuba, and Canada. Before Messrs. Wood & Perot introduced their work into Canada, that portion of the British possessions was supplied from England; but the superior elegance of Philadelphia-made iron-work has driven the English manufacturers out of the market, and Messrs. Wood & Perot enjoy a virtual monopoly of the trade.

In 1858, Wood & Perot had installed sales representatives in cities across the country, and was seeking new avenues of expansion. For a period of time, the firm operated a New Orleans branch called Wood, Miltenberger & Co., after establishing a partnership with a local coal merchant by the name of Charles A. Miltenberger. Located at 57 Camp Street from 1858 to 1861, Wood, Miltenberger & Co. supplied many of the cast-iron balconies, railings, balustrades, and fencing seen in New Orleans’ Garden District. Despite doing a very brisk business, the New Orleans operation was forced to close at the start of the Civil War. The war shook things up in Philadelphia, too, as Elliston Perot moved to New York soon after it ended. However, with the help of two new partners, Irah Case and Thomas Root, Robert Wood continued on until 1879, under the new name of Robert Wood & Co.

My own appreciation for Robert Wood is fairly immense. I admire the company’s business sense, their influence and reach. I am struck by their lasting legacy, by the number of buildings still adorned with their inspired architectural ornament. Mostly, I appreciate the quality and inventiveness of the objects. Robert Wood produced some of the finest and most coveted animal statuary ever made, including the “long-bodied” version of the Newfoundland dog that was made first, in smaller proportions, by Hayward, Bartlett & Co. of Baltimore. Robert Wood also produced a particularly stunning cast-iron stag, the most detailed and well-modeled of them all. When you have a Robert Wood piece in front of you, it’s clear that Wood employed not just technicians, but great artists. Edwin Freedley wrote in 1857 that the Robert Wood company played a vital role in the “adornment of the dwelling-places, breathing-places, and last resting-places of the . . . American people”—and I couldn’t agree more. [Credit: Barbara Israel Garden Antiques.]